Some of You Don’t Read Architectural History and It Shows

On the Critical and Emotional Necessity of Reading in Architectural Education and Practice

Link to my Substack Essay here

Something I am aware of and understand well is that architecture students, generally, do not want to read architectural history or theory. They are interested in questioning, challenging, debating, and discussing, but general perception towards essay-writing is that it is a burdensome task. Something that only consumes what little time they have to explore the subject. Architectural context becomes something to be ‘skipped’, ‘missed’, or completed through ChatGPT and then forgotten.

I can understand this. Architecture is pressurised, highly time-consuming and an extraordinarily demanding career choice. I don’t think many people outside of architecture truly understand the weight of it, (and even until I was exposed to it, I don’t think I did either). It’s a resonant blend of data, information, creative and physical demand, and memory retention that keeps demanding more and more from you.

Reading, in this equation, can easily be summarised or avoided altogether - and it doesn’t help that, (architectural history in architecture education) often carries the lowest credit weighting towards grading. But this is superfluous, as the true issue is what you truly lose when you are not exposed to reading.

Buildings have never been neutral; architects have never truly been passive individuals whose primary aim was to make money. To think that everything is cold and calculated limits the deeper understanding of the human impression, and the awareness of an individual’s life. There are a magnitude of hands that a building passes through on the way to completion, and to limit this as something that is without influence is to remove its humanity.

1. Why Reading Is Seen as Optional (and as a Burden)

In architectural education (as in practice) there is a strong message: build, design, model, render. Additionally, tutoring often privileges production: drawing, digital modelling, studio work. Students are primarily motivated to produce, to present, to compete timely and conclusively. Reading architectural history, theory, or criticism is often seen as peripheral. The effect is that reading becomes additional rather than foundational, an accessory rather than the spinal column of architectural thought.

But reading is the spinal column. It’s the gripping base point of the mind, the vertebrae that connects perception to intention. Reading is the thing that wakes you up at night with ideas, that helps you to relate to buildings, materials, and people. It is the textured, visceral core of architecture itself.

Of course, it is understandable why it’s neglected. Students endure long days of lectures, materials classes, site visits, and deadlines, (not to mention multiple ‘all nighters’ and lack of sleep) the idea of opening another text, to immerse in the argument of a historian or critic, feels impossible. It is easier to skim, summarise, or copy a friend’s notes. But through this you lose the depth of your own context, the layers of meaning behind your designs, and the capacity to ask why, rather than simply how.

Without your lens, and your participation, architectural context becomes superficial. You might recognise a façade type or a precedent form, but you don’t carry the embedded narratives of that form: the colonial appropriation, the gendered assumptions, the economy of labour that built it, the politics behind the funding. Without reading, you are designing and critiquing in a vacuum, which is precisely what the system of pedagogy and practice wants: someone who can produce, but not question.

To skip reading is to relinquish your capacity to critique.

2. Reading as a Gateway to Meaning and Power

Why should you read? Because in reading, you begin to see. You connect your drawing and modelling and form-finding with the lives that built and inhabit architecture, with politics, materials, and labour. There is a magnitude of hands that a building passes through on the way to completion, and to limit this as something that is without influence is to remove its humanity. By reading, you open yourself to those hands. You witness them.

Consider what you already understand instinctively, how a building doesn’t simply appear. It is commissioned, designed, constructed, inhabited, modified, and sometimes abandoned. The individuals and forces behind it include the client or state, the architect, the engineer, the contractor, the workers, the local community, and future generations, etc. If you don’t read architectural history, you miss the fact that many of those hands were not neutral, they had their own ideologies, desires, and fears, and the building reflects these back to you.

Deyan Sudjic’s The Edifice Complex: The Architecture of Power (2005) traces precisely this: the relationship between architecture, ego, and domination. Sudjic writes that architecture “must be understood as an expression of power and as a weapon, or form of propaganda.” (Sudjic, 2005).

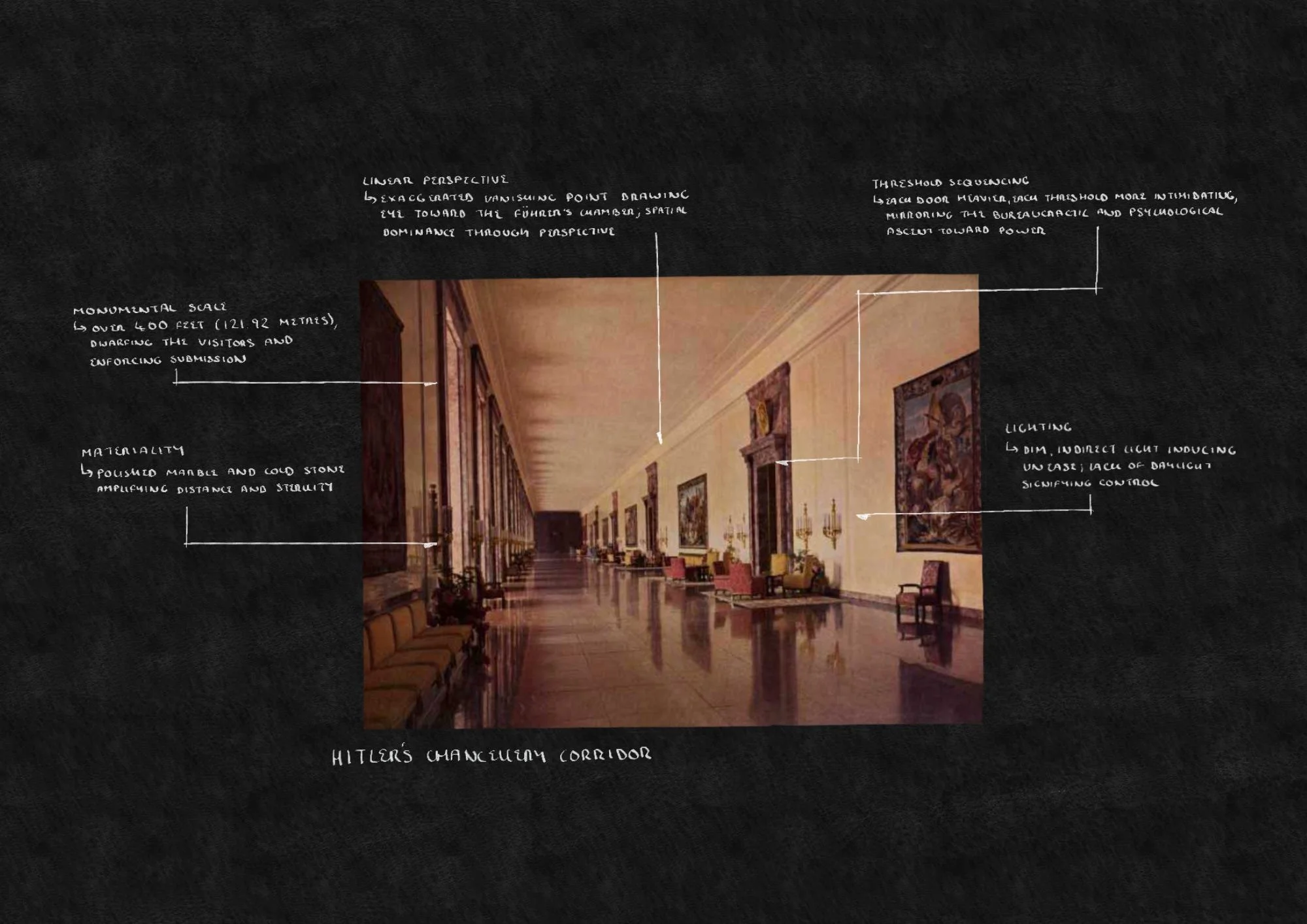

Nowhere is this clearer than in Hitler’s New Reich Chancellery in Berlin. The corridors were vast (more than 400 feet long) intentionally disorienting, designed to induce a sense of inferiority and awe. The building’s spatial strategy was psychological warfare: as Sudjic notes, “the Chancellery was built to intimidate, to make its visitors feel small, fearful, insignificant”(Sudjic, 2005). Reports circulated that visitors were so overcome by the oppressive atmosphere that some fainted; the monumental scale was meant to crush, not to comfort.

Architecture manipulates perception before it even communicates intention. It shapes how bodies move, how they feel, and how they submit. Without reading and understanding such examples, you risk designing spaces that unconsciously replicate manipulation rather than subvert it.

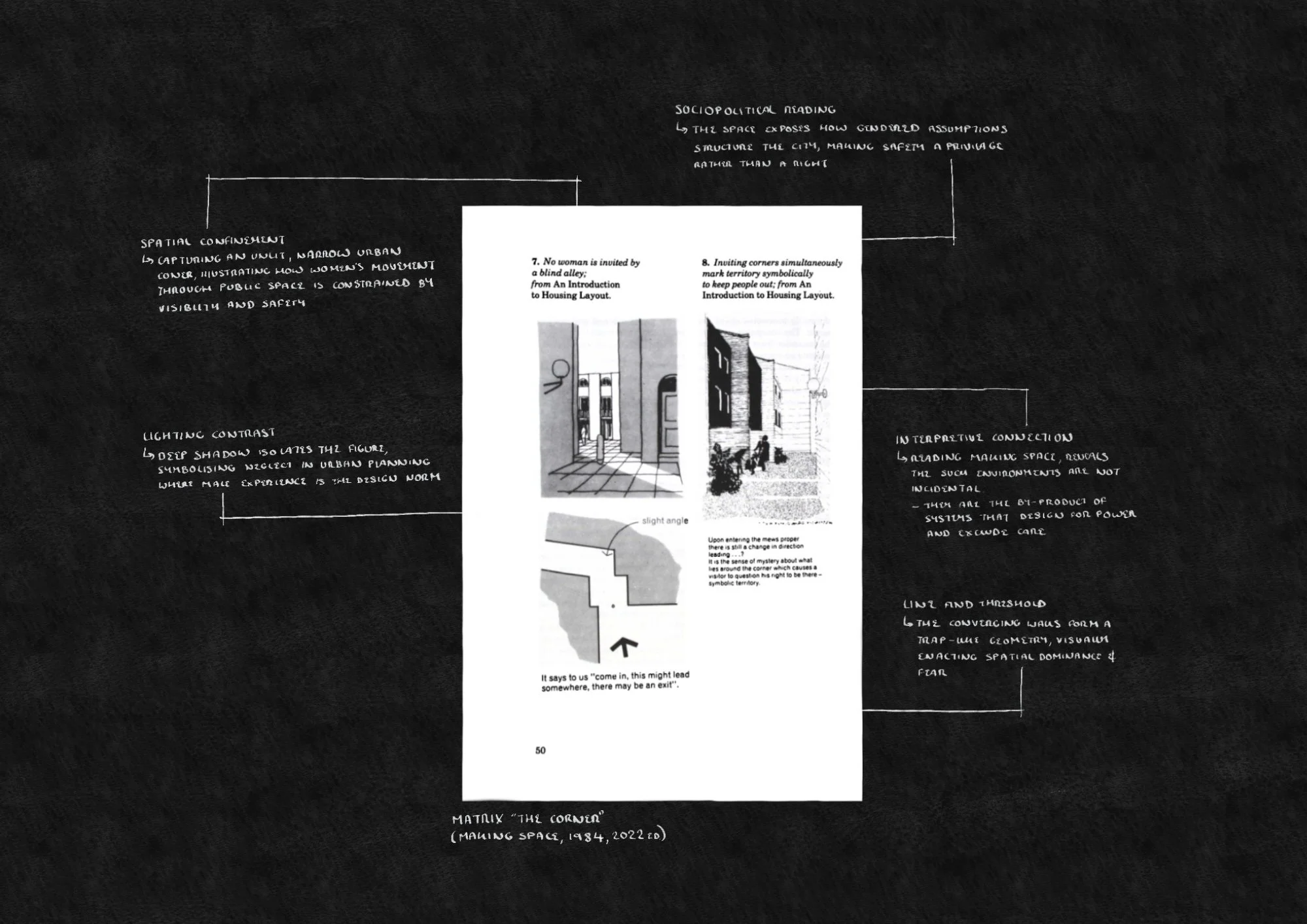

Matrix’s “Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment” (1984; 2022 ed.) exposes a different form of spatial control: the everyday gender bias of the built world. The authors demonstrate how cities, transport systems, and workplaces are designed primarily around male patterns of occupation, from public lighting that neglects women’s safety at night to domestic layouts that reinforce unpaid care labour. The famous “corner in the city” photograph, illustrating an unlit, narrow turn that forces women into vulnerable isolation, captures this spatial gendering perfectly. Reading Making Space forces you to recognise that what feels “neutral” often isn’t. Space is coded, exclusionary, and political.

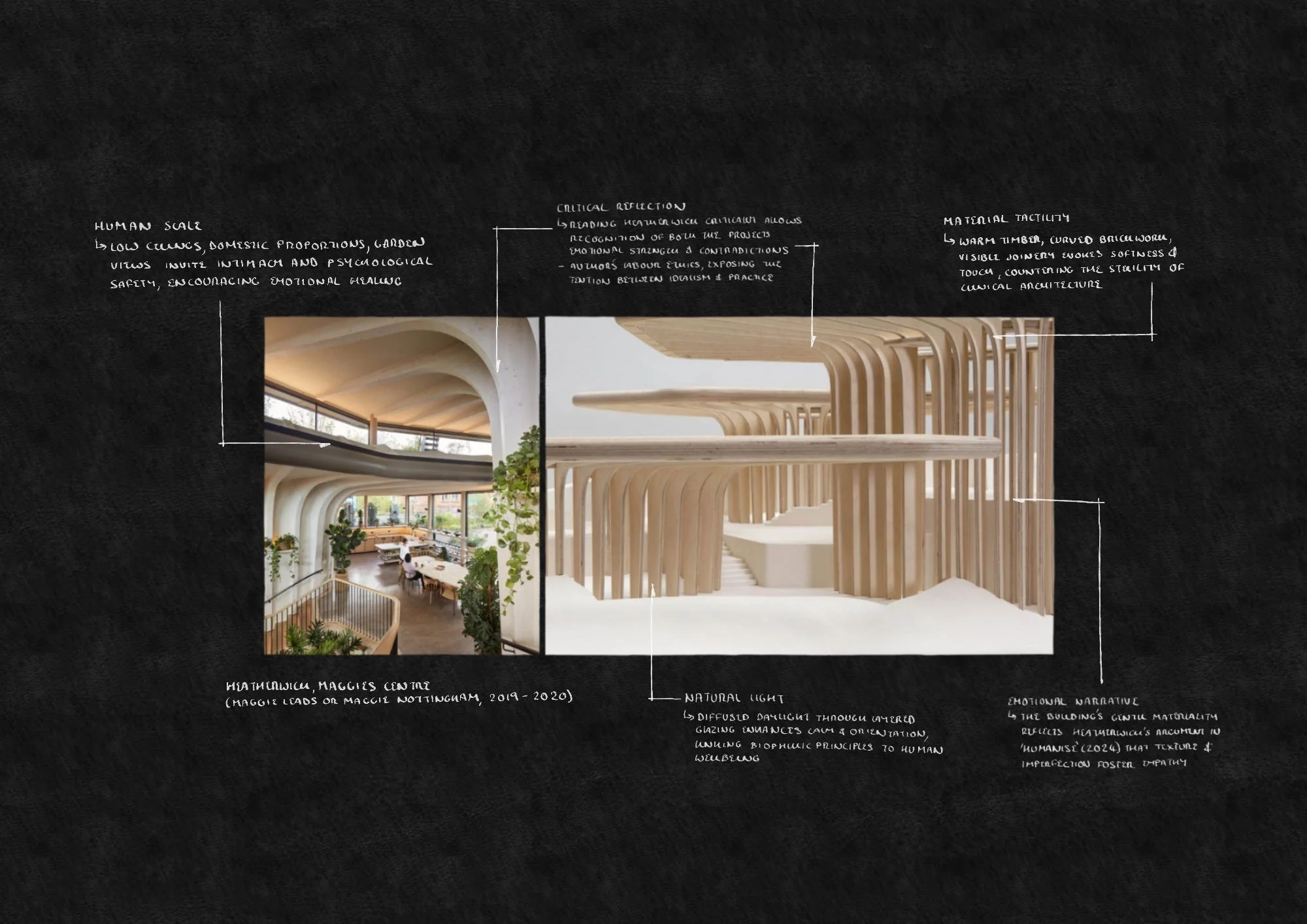

Similarly, Thomas Heatherwick’s “Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World” (2024) advances a call for emotional connection through materiality. He argues that soulless, homogenised design, “too flat, too plain, too monotonous”, contributes to psychological alienation. While his argument for sensuality and tactility is persuasive, reading critically also means acknowledging contradiction: Heatherwick himself has faced allegations of exploitative studio culture and labour issues. This complicates the narrative of “humanising design”: who gets to claim humanity, and at whose cost? Reading his book through a critical lens enables you to see both the value of his ideas and the hypocrisy of their conditions.

Reading never simply “give you tools.” It forces you into confrontation with architecture’s contradictions. It positions you between admiration and suspicion, between the material and the moral. To read is to wrestle with it, to allow yourself to be unsettled by it.

3. What You Lose When You Don’t Read

Avoiding reading is not a neutral approach, it carries consequences with you. If you design without reading, you are more likely to reproduce stylistic tropes without understanding their origin. In positions of power (which as an architect you will hold) you risk repeating the past without awareness. You risk being manipulated by architecture rather than using architecture to question and challenge manipulation itself.

a) Your own loss of agency.

Without history and theory, you become a receiver, not a producer, of meaning. Buildings begin to think for you. They embed assumptions you never interrogated (i.e. nationalism, elitism, exclusion) and you unknowingly perpetuate them. Reading acts as the bridge between intuition and intentionality.

b) Your own loss of ethical awareness.

Reading illuminates the networks of labour, extraction, and inequality that make architecture possible. To ignore these is to participate in them uncritically. Architecture is never neutral, even silence is complicity.

c) Your own loss of creative richness.

Reading extends your imaginative reach. It gives you other lenses (phenomenology, feminism, post-colonial theory, ecology, etc.) through which new spatial possibilities emerge. Without it, your work risks orbiting safely within the sanctioned aesthetics of the moment, mistaking novelty for originality. Reading allows architecture to speak in dialects rather than slogans.

d) Your own loss of meaning.

Architecture is lived and felt. If you dismiss reading, you design objects instead of places. You design images instead of experiences. A building may look good in a render, but if it ignores the story of its site and community, it lacks legitimacy, and it all just becomes an empty performance of culture.

4. How reading changes the way we see buildings

Reading transforms your perception: buildings become legible texts, layered with ideology and labour.

Case 1

The Edifice Complex

Sudjic exposes the rhetoric of power embedded in architecture. Hitler’s Chancellery demonstrates how architecture can dictate emotion, how scale and sequencing become instruments of fear. Reading this shifts your view from admiration to interrogation, you see the domination.

Case 2

Humanise

Heatherwick correlates architectural blandness with social malaise, calling for emotional and tactile design. For example, his discussion of the Maggie’s Centres (small cancer-care buildings that emphasise warmth, texture, and domesticity) illustrates how material softness can restore dignity. Reading this allows you to connect psychology, materiality, and care, even as you remain alert to the contradictions in the author’s practice.

Case 3

Making Space

Matrix’s feminist critique reframes the city as a site of exclusion and fear. The “corner” example, a dimly lit urban junction, becomes a metaphor for how design decisions structure vulnerability. Reading this could compels you to ask: who is this city for? Who feels safe here? What invisible geographies of fear have we drawn into our maps?

Through reading, yourself as an individual, begin to decode buildings not as static objects but as dialogues between author, inhabitant, and system. You start to ask: When was this built? Who funded it? What ideology is wrapped into it? You develop interpretive depth, a new sightline through which the built world becomes articulate.

5. Reading as Resistance and Responsibility

In a profession driven by deadlines, clients, and software, reading might appear as a luxury. But reading is both resistance and responsibility.

Resistance

The dominant model of architecture is now fast, visual, market-driven. It values spectacle over substance. Reading intentionally slows you down, resisting the velocity of production while also actively asking you; Why this form? Why this material? Why this place? and that you answer with thought rather than trend. Reading reconnects you with your own intellectual and emotional spine.

Responsibility

Architecture affects everyone, consciously or not. It shapes communities, environments, and identities. If you neglect reading, you neglect empathy. You build for the client but not for the community, for the profit but not for the person. In the current climate (with housing crises, continuous inequality, and ecological collapse, to name a few) architecture cannot afford ignorance.

Reading architectural theory allows you to see people’s souls through buildings. You begin to recognise how your own thinking is shaped by patriarchal values, capitalist underpinnings, colonial legacies, and stylistic ideologies. These forces influence you. To understand a building fully, you must understand the world that built it.

To understand a building fully, you must understand the world that built it.

Conclusion

Some of you don’t read architectural history and it shows. If you dismiss reading as optional, you allow architecture, and not yourself, to do the thinking. You surrender agency to the client, the software, the trend, the image. But through critical engagement, you reclaim that agency. Architecture is a human act embedded in time, labour, politics, and culture. There are a magnitude of hands that a building passes through on the way to completion, and to limit this as something that is without influence is to remove its humanity.

In your career, in your studio, in your reading hours, commit to the books, the essays, the documentaries. They are not obstacles to design but enablers of your own depth. They offer you sight beyond the form and conscience beyond the render.

To read is to care, and to care is to design ethically.

References

Boys, J. et al. (2022) Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment, 3rd edn. London: Verso.

Heatherwick, T. (2024) Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World. London: Penguin.

Sudjic, D. (2005) The Edifice Complex: The Architecture of Power. London: Penguin.