The Ethics of Repair

Learning from fabric & how conservation teaches us to act with care, not control

In architecture and conservation, repair is a technical act and an ethical one. It demands judgement, restraint, and an awareness of both the material and the moral implications of intervention. What we choose to repair, what we choose to leave, and how we choose to act upon the past reveals much about our collective values.

The lectures by Matthew Slocombe (The SPAB Approach to Understanding and Protecting Built Fabric) and Christina Emerson (Historic Building Controls) together illuminate this ethical landscape. Through ‘The Repair of Old Buildings Course’ they outline the historical, legislative, and philosophical frameworks that define how we engage with old buildings, and, more crucially, what we owe to them.

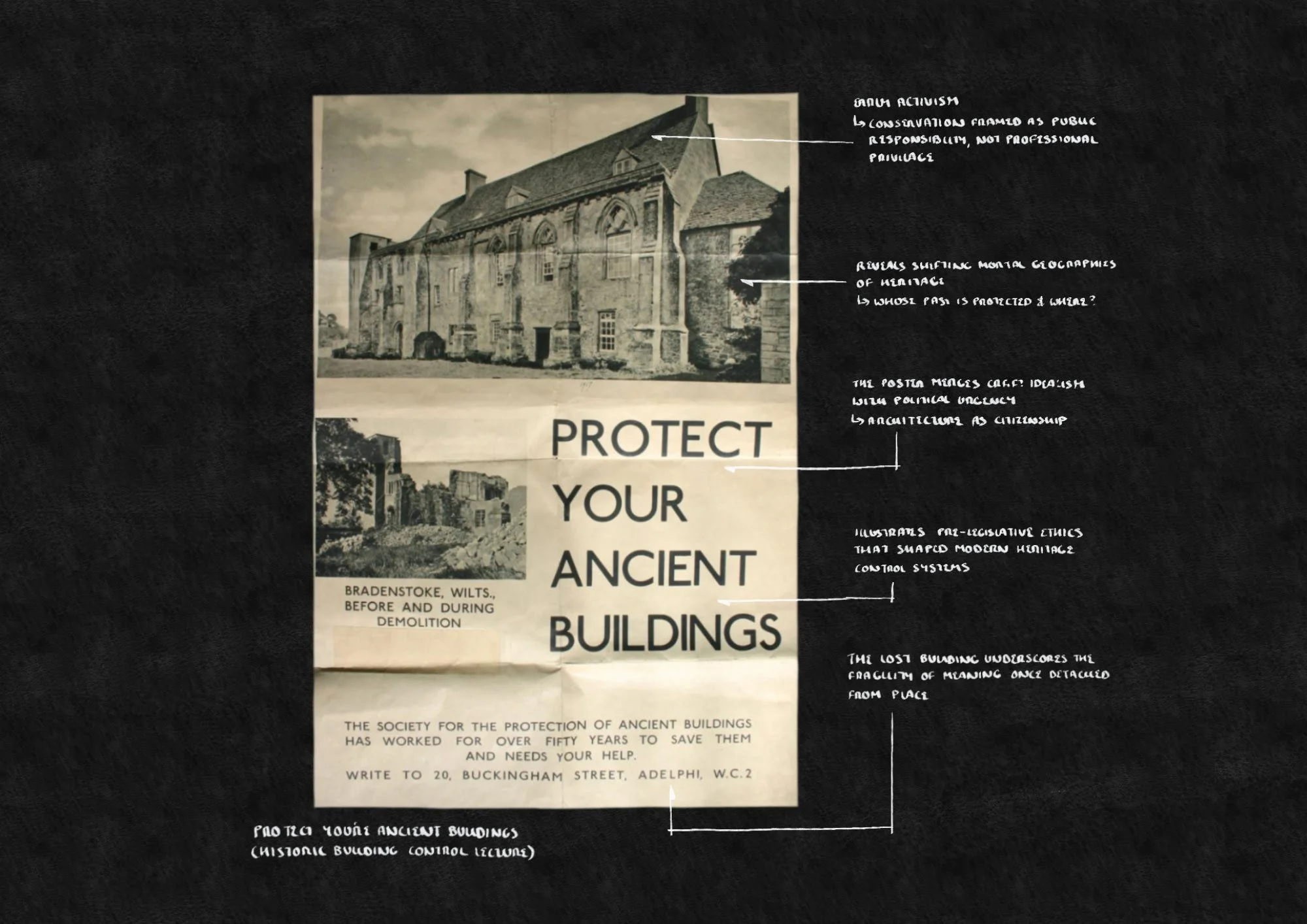

Origins of an Ethic: The SPAB Manifesto

The modern British conservation movement was founded not in technical manuals but in moral outrage. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), founded in 1877 by William Morris and Philip Webb, emerged in reaction to the destructive zeal of Victorian “restoration.” Morris, echoing John Ruskin’s ‘Seven Lamps of Architecture’ (1849), declared restoration to be “a lie from beginning to end.” For Morris, to restore was to falsify history, to erase the authentic traces of age, use, and change that made a building meaningful.

In the SPAB Manifesto, Morris argued that “our descendants will find [ancient buildings] useless for study and chilling to enthusiasm” if restoration continued unchecked. Morris advocated instead for “Protection in the place of Restoration,” (SPAB 1849) urging care, maintenance, and honesty of intervention. This philosophy, of doing only what is necessary, and never what is conjectural, remains the cornerstone of conservation ethics today.

This early moral framing of conservation established repair as an act of humility. The aim was to preserve and to understand To repair a building became to acknowledge its temporal depth, to act as caretaker and custodian, rather than a creator. From this position of restraint, the SPAB’s approach evolved into a guiding principle of architectural ethics: that the material fabric of a building holds its history, and that to alter that fabric without understanding it is to erase the evidence of human life itself.

2. The SPAB Approach: Protection of Fabric

The SPAB Approach translates this moral philosophy into practical methodology, the protection of fabric as both ethical duty and empirical evidence. Slocombe’s lecture emphasised that a building’s fabric is the “primary source from which knowledge and meaning can be drawn.” (Slocombe, 2025). It records style, social and technological history; expanding the shifts in taste, craft, and use. Every surface and imperfection actively presenting a narrative.

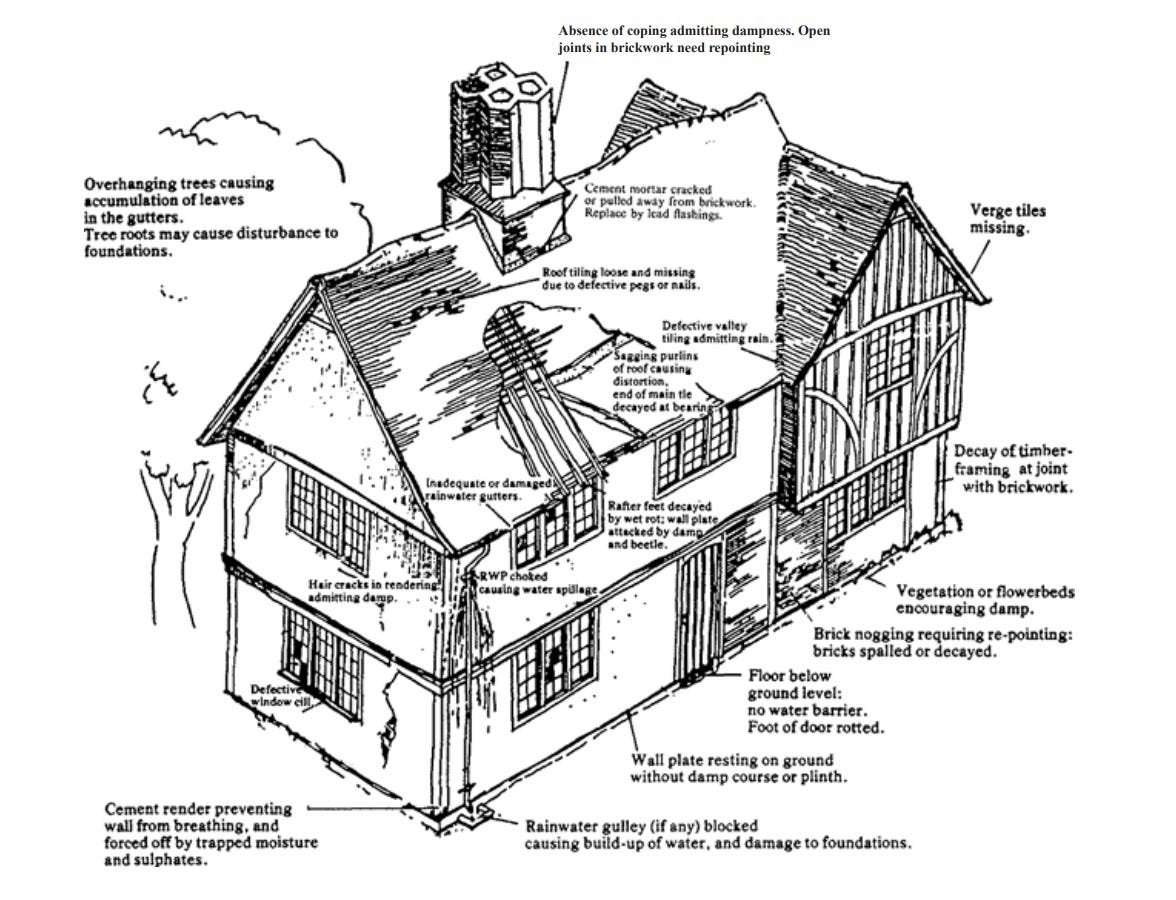

Modern SPAB guidance maintains that the conservation of old buildings should prioritise minimal intervention: “stave off decay by daily care,” “prop a perilous wall,” and “mend a leaky roof” (SPAB, 2025) but otherwise, do no more. There ‘conservative repair’ method ensures that interventions are legible, localised, and reversible. The use of compatible materials (lime mortar rather than cement, for example) respects the building’s breathability and structural behaviour, aligning ethics with physics.

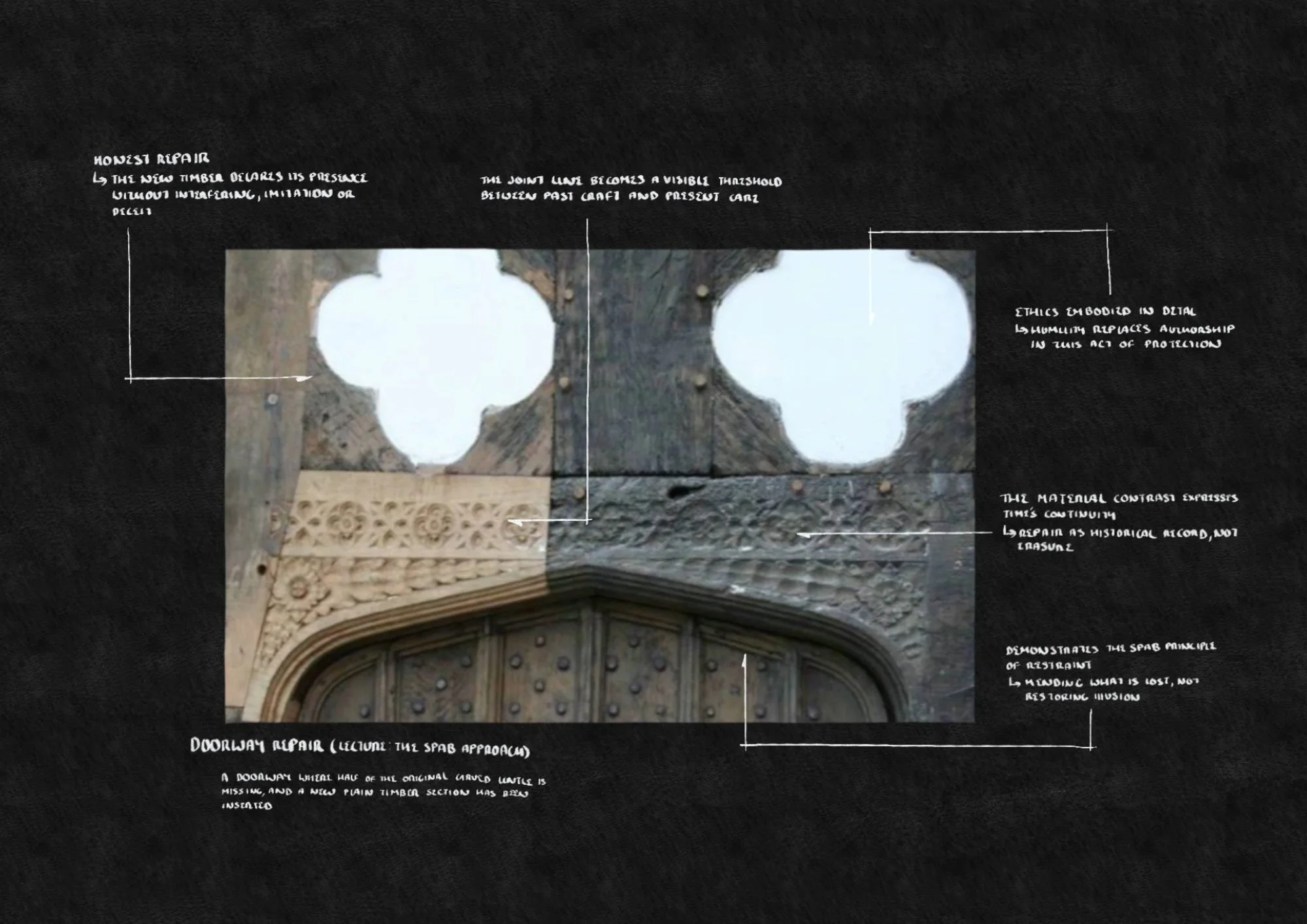

Such restraint is not regarded as passive, it aims to reflect a deeper understanding: before acting, one must comprehend the structure, materials, and history. The craftsman’s hand becomes interpretive rather than transformative. As Philip Webb demonstrated in his tile repair technique, repair is a dialogue between old and new, where the new acknowledges its subservience to the existing. This philosophy resists the impulse to “fix” or “finish.” Instead, it embraces imperfection as evidence of life, an ethics of material empathy that sees in every weathered surface the accumulated dignity of time.

3. From Philosophy to Policy: The Legislative Framework

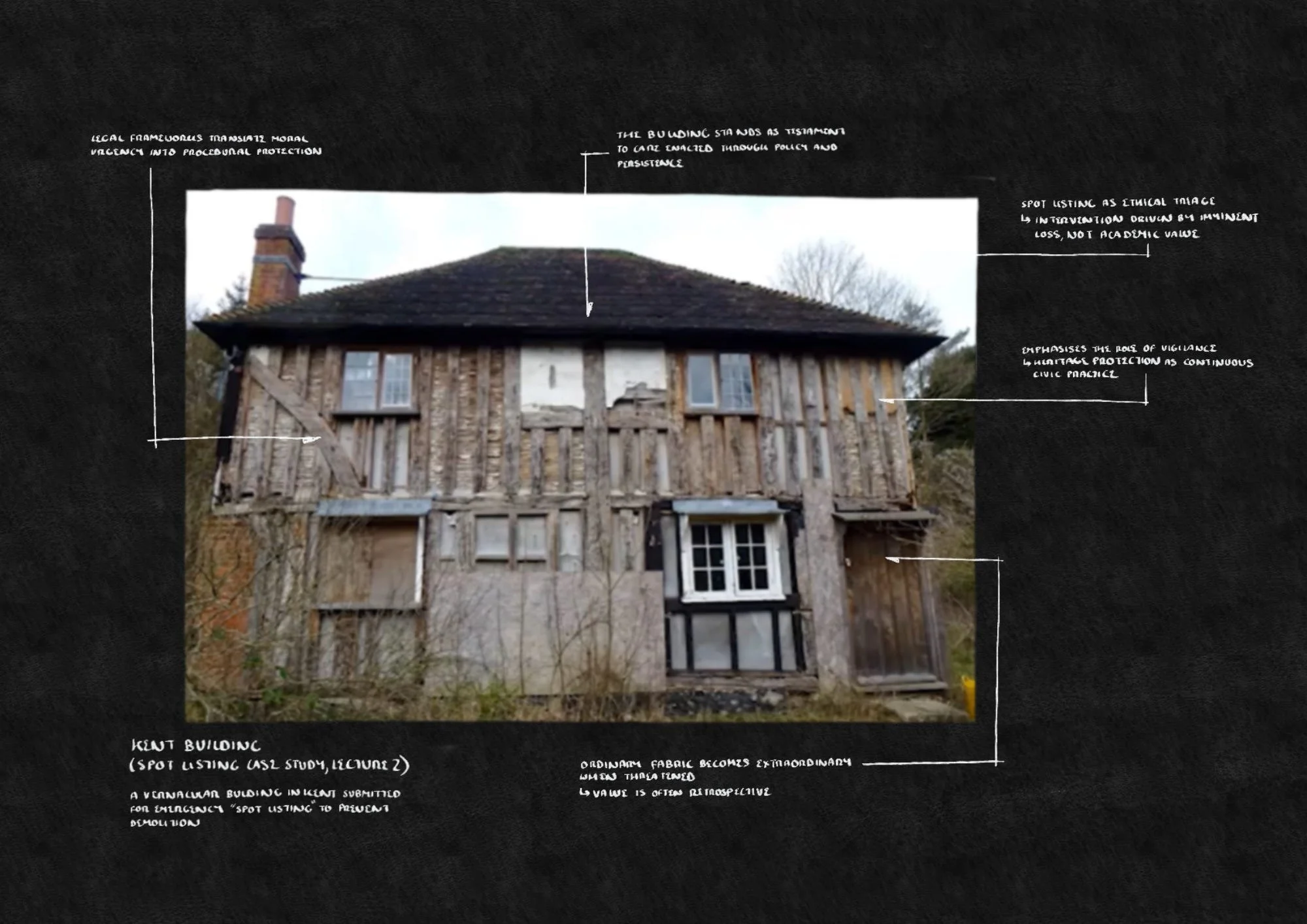

If SPAB supplied conservation with its moral compass, modern heritage legislation provided its framework for action. As Christina Emerson outlined, the UK’s heritage protection system developed through successive acts: the Ancient Monuments Act (1882), Town and Country Planning Acts (1947, 1968), and the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act (1990) (Emerson, 2025). These collectively established the mechanisms of listing, designation, and control, formalising the ethical concerns of Morris into statutory duty.

Section 16 of the 1990 Act requires decision-makers to give “special regard to the desirability of preserving the building or its setting or any features of special architectural or historic interest,” (Emerson, 2025). This enshrines the SPAB ideal, the presumption of preservation within legal process. Later frameworks, such as the National Planning Policy Framework (2019), extend this principle, requiring “clear and convincing justification” for any harm to heritage assets. Legislation therefore acts as institutionalised ethics. Where Morris originally appealed to conscience, contemporary conservation appeals to law. Although, both rely on individual interpretation. The definitions of “significance,” “harm,” and “enhancement” remain subjective, demanding judgement that is at once technical and moral. In this sense, heritage legislation does not replace ethical reflection, instead it formalises it. The conservation officer, architect, or planner must still exercise discretion, weighing tangible explanation against the intangible, and the rights of present owners against the responsibilities owed to future generations.

4. Repair as Moral Decision & When to Intervene

As outlined act of repair sits on a spectrum between neglect and reconstruction. The ethical challenge lies in discerning when doing nothing is care, and when inaction becomes decay. SPAB’s “conservative repair” principle encourages minimal intervention, but not entire abstention. As Slocombe emphasised, the society recognises that “localised reinstatement may be entirely sensible and justified” if it is clearly distinguishable and structurally necessary (Slocombe, 2025). To “leave it alone” is ethical only when stability and safety permit. This is supported by broader international charters such as the ICOMOS Burra Charter, which allows reconstruction “as part of a use or practice that retains the cultural significance of the place.” In other words, the context matters: the ethics of repair are culturally contingent, informed by the meaning communities attach to built form.

Ethical conservation, therefore, is not rigid. It requires balancing authenticity of fabric with continuity of use. An empty, perfectly preserved ruin may satisfy purists, although the living, adapted building sustains cultural relevance. Both outcomes can be ethical provided they are justified, transparent, and proportionate. Ultimately, the ethics of repair lie in the reasoning that underpins each act. It is the thoughtfulness of repair that constitutes its moral integrity.

5. Custodianship and the Future of Fabric

Conservation is, at its centre, an act of trusteeship, a recognition that we hold buildings in temporary custody. The SPAB’s oft-repeated maxim, “we are only trustees for those that come after us,” (SPAB, 2025) captures this intergenerational contract. Preventative maintenance (the acts of clearing gutters, repairing downpipes, maintaining drainage, etc.) embody this ethic. Similarly, the legislative frameworks that Emerson detailed (from listing to enforcement notices) all reinforce this idea of stewardship. Unauthorised works, demolition, or neglect are not merely regulatory breaches; they are breaches of trust. The aim of policy is to preserve the conditions for continued meaning.

To repair ethically, then, is to accept responsibility and accountability. It is to see buildings not as inert heritage objects, but as active participants in cultural continuity. The mark of good repair is honesty, whereby an intervention that declares itself modestly and integrates respectfully.

Conclusion | Repair as a Moral Language

The SPAB and its successors have taught that conservation is not a science of surfaces, but an ethics of care. Through policy, practice, and philosophy, the act of repair becomes a form of moral reasoning, that values endurance over novelty and continuity over replacement.

To repair is to acknowledge both the fragility and resilience of built fabric by participating in an evolving dialogue. “It is for all these buildings, therefore, of all times and styles, that we plead,” The intention of SPAB’s approach is to repair how we think about what endures.

References

Morris, W. (1877) The SPAB Manifesto. Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

Ruskin, J. (1849) The Seven Lamps of Architecture. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Slocombe, M. (2025) The SPAB Approach to Understanding and Protecting Built Fabric. Lecture, Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

Emerson, C. (2025) Historic Building Controls. Lecture, Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

Historic England (2019) National Planning Policy Framework. London: Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities.

ICOMOS (2013) The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance.

Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (2017) The SPAB Approach. London: SPAB.