Why We Still Need Physical Books

Tactility, Presence, and the Politics of Owning What You Read

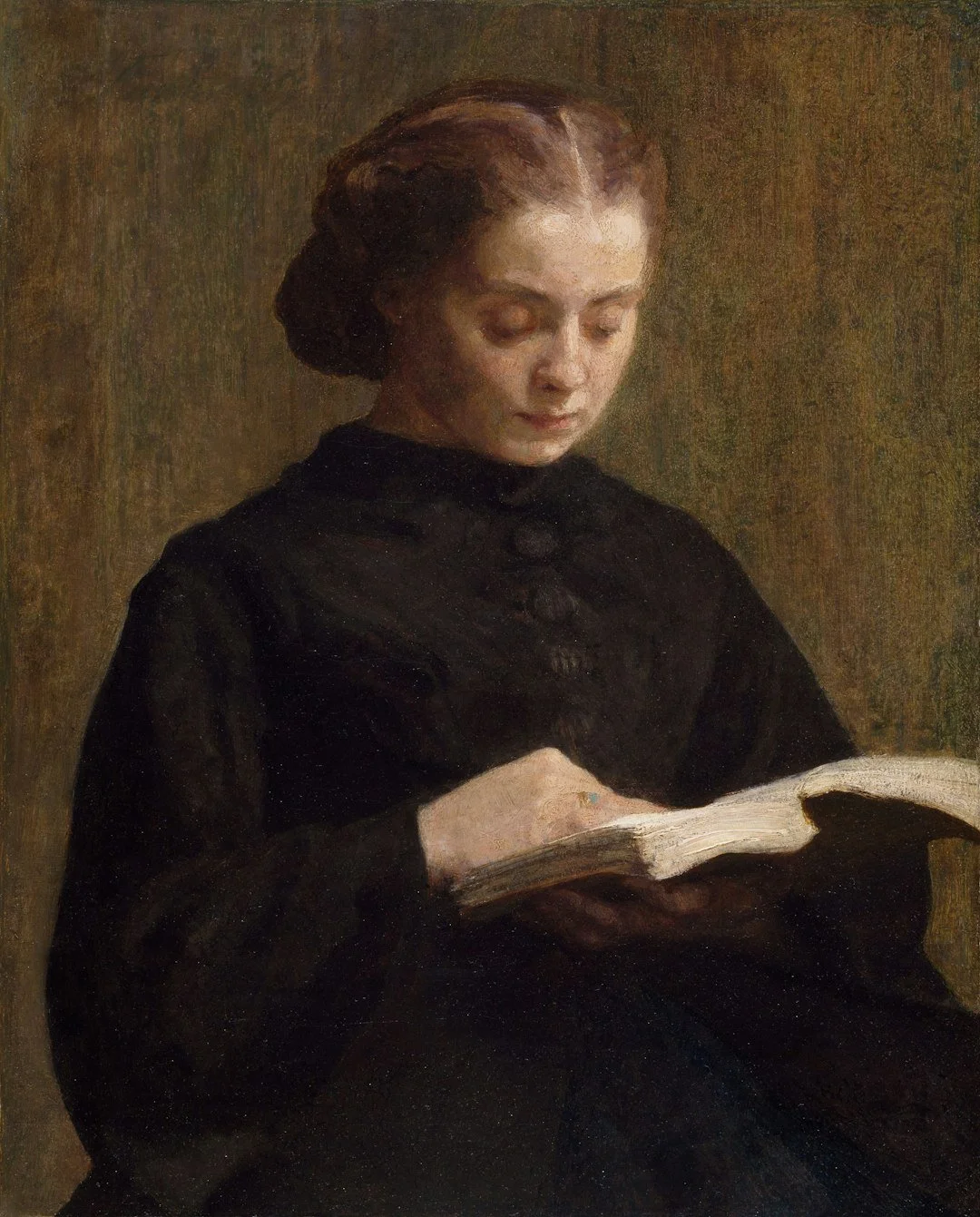

There is a particular kind of awareness that only emerges when you move through the world with a physical book. Its weight shifts against your shoulder as you walk, its spine presses gently against the contents of your bag, and when you sit down, it becomes an object you orient yourself around. Even when placed on a table, held in the lap, or tucked beside a cup of tea. A printed book situates you. It operates as a small, portable locus of attention, a rectangular anchor that grounds the body in space and restores a sense of presence that digital devices quietly erode.

In a culture increasingly shaped by screens, physical books offer an experience of reading that is embodied. Interrupting the posture of digital consumption (that hunched, alienated curvature we assume when we fold ourselves). Digital reading may offer ease, but for able bodied individuals it rarely offers genuine connection. By contrast, the tactility of a printed book (the grain of the paper, the friction of a page turning, the visible and spatial progression through the text) draws you back into the local world. Inviting you into a slower tempo, a calmer mode of cognition, and a form of attention that is rooted.

When I read a physical book, I am locating and re-situating myself. The experience is sensorial, and it is an encounter with an object that carries its own presence, and in that presence lies the quiet but necessary reminder that is a bodily and spatial involvement.

Reading as Embodied Practice

A physical book transmutes reading from an abstract cognitive task into an embodied experience that situates you in your immediate environment and encourages a slower, more attentive way of being.

When you carry a printed book, you carry its weight. It shifts inside your bag, you are aware of its presence. You could place it down on a table and it occupies space like any other crafted object. Those small interactions form a subtle, constant dialogue between your body and environment. By contrast, digital reading often adopts a common default posture, that is hunched over a glowing screen like a prawn, shoulders forward, eyes strained. The device is closed off from the world around you. Its design encourages a posture of withdrawal rather than engagement.

Embodied reading matters because it integrates thinking with movement. The book becomes part of your physical rhythm. You open it while sunlight changes across the page, you close it during a bus ride, you dog-ear a corner or have a curated bookmark, etc., and its these gestures build a sensory memory of place. Digital interfaces flatten this experience into uniformity, it is the same blue toned cool rectangle regardless of mood, light, setting, or season. For individuals working in material fields, the relationship between hand, object, and environment is fundamental. A book behaves like any other crafted object, and reading it becomes an act of grounding, a way of being present in local space rather than abstracted into the digital ether.

The Brain Prefers Paper and Why Physical Books Foster Deep Thinking

Print reading also supports deeper comprehension, stronger memory, and healthier cognitive engagement than digital reading the physical properties of paper activate neural pathways that digital interfaces do not. A recent article by New Scientist demonstrates that reading paper “enhances comprehension and recall, strengthens neural pathways, and improves memory and concentration,” (Thomson, 2025). Turning pages creates a tactile sequence that the brain uses as a spatial map of the text (Thomson, 2025). This supports what cognitive psychologists call “deep reading”, the slow, reflective mode of attention required for critical thinking (Thomson, 2025).. Screens, by contrast, encourage skimming and multitasking, which fragments attention even when we are attempting to focus.

The physicality of a book provides your mind anchors. Page thickness, layout, the physical progression from beginning to end, all of these establish a sensory framework that supports memory consolidation. Digital reading lacks these spatial cues. It treats text as an endless scroll with no physical boundaries, weakening our ability to retain and integrate information. For example, when I read laborious texts, I need my mind to slow down and encourage the same kind of patient, embodied attention that architectural and craft knowledge require.

Ownership, Autonomy, and the Politics of Digital Precarity

Owning a physical book is now more of a political act. Granting freedoms that digital books (which are usually licensed rather than owned) cannot guarantee. Digital books are governed by restrictive licensing and DRM (Digital Rights Management). As the Electronic Frontier Foundation notes, e-book platforms can track your reading, prevent sharing, change access conditions, or remove content entirely (EFF, 2024). Amazon’s Kindle ecosystem has made it explicit, you do not “own” your Kindle books, you are granted a revocable license (EFF, 2024). This is why, in 2009, Amazon remotely deleted copies of 1984 from users’ devices when a licensing dispute arose, a moment that exposed how fragile digital “ownership” truly is (EFF, 2024).

Digital libraries are also vulnerable to subscription changes, data breaches, server shutdowns, or account suspensions. If a platform closes, your library disappears overnight. Several cases in recent years (including the closure of Playster, the removal of DRM-free files from certain publishers, and price restructurings that locked users out of previously purchased content) demonstrates the fragility of digital collections (EFF, 2024). A physical book avoids these vulnerabilities. You can lend it, annotate it, burn it, resell it, give it away, or keep it until the end of your life. Its ownership is non-negotiable and you’re own. No corporation can revoke your access or alter its content. This stability matters, especially in an era where much of our cultural memory is stored on rented platforms. To own a book is to maintain sovereignty over what you read and how you read it.

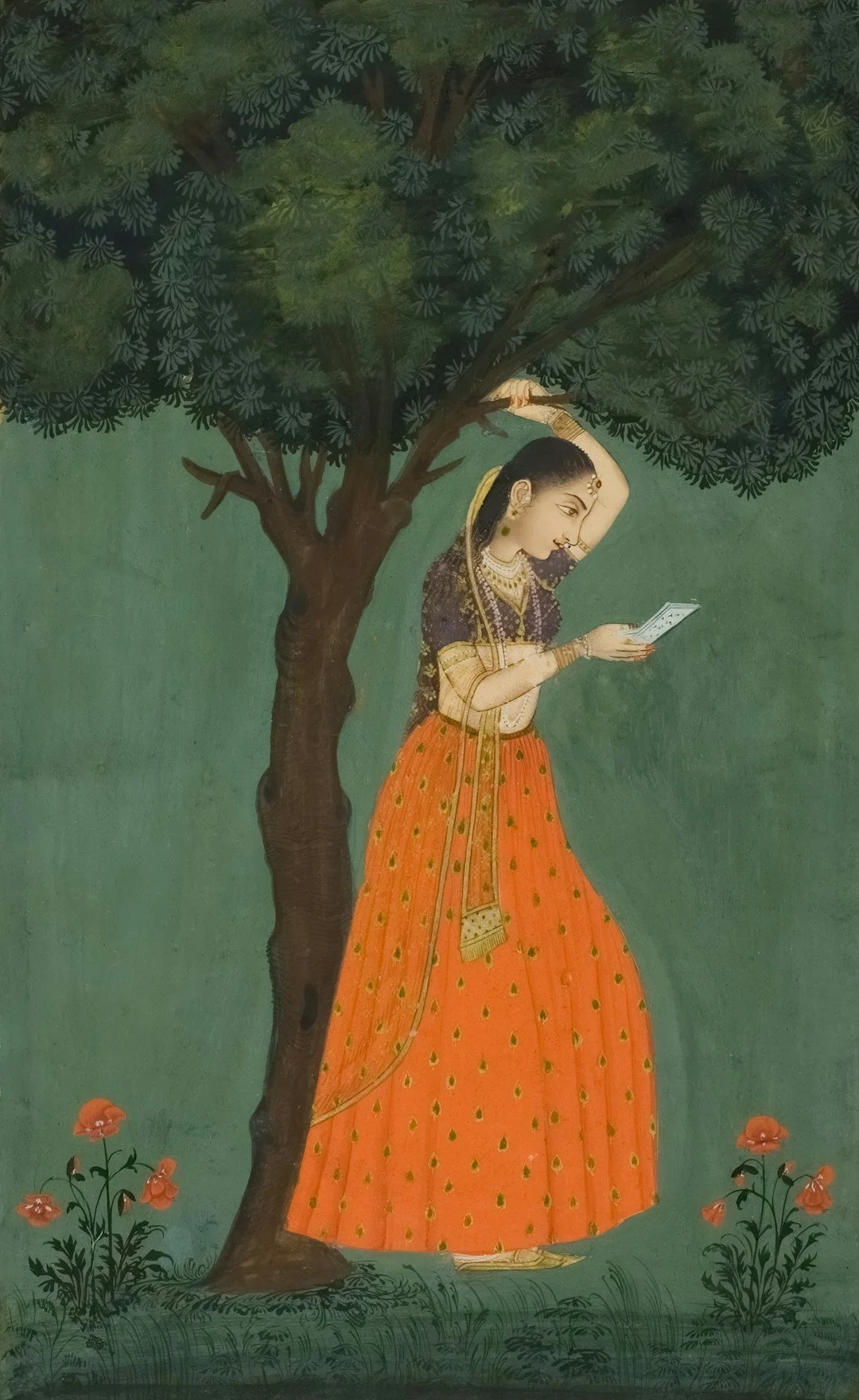

Creative Agency and the Sensory Life of Books

A printed book is a sensory experience that is handled, carried, annotated, lived with. These interactions become part of your reading experience and shape your personal intellectual history. When you annotate a margin, crease a page, slide a ticket between chapters, or accidentally spill coffee on a corner, you should be aware that you leave traces of your life within the book. These marks document your thinking the same way tool scratches document the life of an object, and digital reading erases this intimate archive. Marginalia becomes a menu option, highlighting becomes a fluorescent abstraction and the book’s material biography (and your own) are flattened into a sterile interface. In my own practice, materials are never passive. Wood argues and remembers what you did, brushes are worn by hands, and buildings wear the weather; books operate the same way. They are artefacts with a life cycle, reading physically is participating in that cycle.

The Book as a Material Anchor in a Disembodied Age

Physical books persist because they offer something digital reading cannot; a grounded, embodied, and politically autonomous experience of knowledge. They reconnect us to our environment, and they support our cognitive depth. They give us ownership rather than access, while also aging with us. They are slow in the best possible way.

In a contemporary culture defined by speed, data extraction, and placeless screens, the printed book remains a profoundly local object. As a companion that preserves attention and provides a mirror to ourselves.

References

Electronic Frontier Foundation (2024) Digital Books and Your Rights: A Checklist for Readers, EFF. Available at: https://www.eff.org/wp/digital-books-and-your-rights (Accessed on: 25.11.2025)

New Scientist (2025) Thomson, H. “Is reading always better for your brain than listening to audiobooks?”, New Scientist, Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2497112-is-reading-always-better-for-your-brain-than-listening-to audiobooks/#:~:text=The%20benefits%20of%20reading&text=Firstly%2C%20it%20encourages%20%E2%80%9Cdeep%20reading,only%20read%20newspapers%20or%20magazines (Accessed on: 25.11.2025)