Building Justice: Reclaiming Colonial Architecture Through Critical Practice

Reflection to Responsibility & Confronting Colonial Legacies in Architectural Practice

Link to my Substack essay here

The RIBA Academy seminar Reclaiming Colonial Architecture (7 May 2025), led by Professor Tania Sengupta (UCL) and Dr. Stuart King (University of Melbourne), offered a profound engagement with colonial legacies embedded in the built environment and material culture. Framing colonial architecture as an ongoing terrain of contested meanings, the speakers called for an active, justice-oriented architectural practice. Drawing on global case studies, historical resistances, and decolonial theoretical frameworks, the session reimagined land, cities, buildings, and “things” as sites of both trauma and transformation.

i. Architecture as a Living Legacy: Colonialism’s Continuities and Contestations

The built environment continues to bear the imprint of colonial ideologies, often persisting as ‘naturalised’ or invisible elements in contemporary urban and rural landscapes. King and Sengupta cited examples such as colonial structures in Redfern, Sydney, now gentrified yet still spatially and socially segregated, as instances of how architectural forms can reinforce historical injustice under the guise of heritage (Sengupta & King, 2024). Similarly, the transformation of Kartavya Path in New Delhi, formerly Rajpath, was presented as an act of political re-inscription rather than true decolonisation.

The image of a Black Lives Matter mural in Hudson, New York, juxtaposed with historical plans of Odesa, Ukraine, served to illustrate how colonial urban imaginaries continue to structure global cities in racialised and exclusionary ways (Sengupta & King, 2024, p.6). These images underscore how colonialism is a set of spatial practices continually reinscribed on the land. These examples reveal how colonial legacies remain embedded in material form and spatial logic, shaping contemporary cities and landscapes in ways that sustain inequality. As Hartman (2019, pp.3–4) observes,

“the ghetto is a space of encounter,”

one where colonial ideologies persist through spatial containment and marginalisation. Recognising these continuities is essential for developing responsive architectural ethics and urban strategies.

ii. Historical Acts of Resistance: Rebellion, Reclamation, and Refusal

Critical architectural practice must be informed by historical and transnational traditions of resistance, particularly those that directly opposed the spatial and material tools of colonial control. This lecture highlighted uprisings such as the 1859–60 Indigo Rebellion in colonial India and the Chipko movement of the 1970s, both of which challenged the extractive logics underpinning colonial land use policies. These movements, though often omitted from architectural discourse, were fundamentally about space, territory, and ecological justice.

The continued presence of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra, founded in 1972 and still active, was presented as a living monument to Indigenous resistance and a model of spatial sovereignty. Similarly, the Anti-Apartheid protests in Johannesburg and Black liberation movements in the U.S. were shown to have explicit spatial dimensions, confronting both symbolic and material structures of segregation. These histories reveal that architecture has always been a battleground; where space is contested, reclaimed, and reimagined. As Frederick Douglass insisted,

“If there is no struggle, there is no progress” (Douglass, 1845).

Incorporating such resistant genealogies into architectural pedagogy challenges the assumption that design is politically neutral and instead demands a practice rooted in solidarity and justice.

iii. Beyond the Metaphor: Reparation, Decolonisation, and the Ethics of Return

This lecture argued that “decolonisation is not a metaphor” (Tuck & Yang, 2012), but a material and spatial imperative; one that must engage with restitution, repatriation, and reparative design.

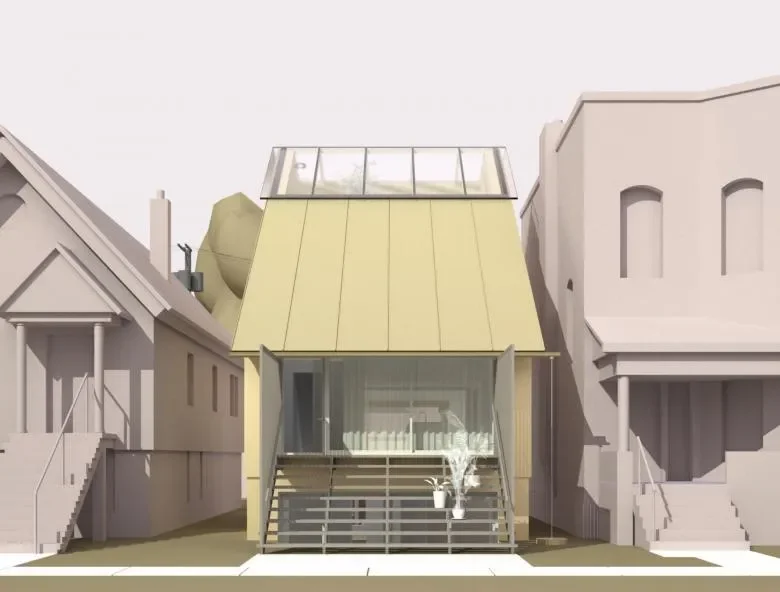

The “infill housing” project by Riff Studio in Chicago (2019, 2023) was presented as a concrete example of reparative urbanism, seeking to address historic housing discrimination through community-led, small-scale interventions (Sengupta & King, 2024). Rather than abstractly “decolonising” architecture, these designs materially redistribute space and resources. Similarly, the museum for repatriated artefacts of the Lobi peoples in West Africa (Aina, 2021) exemplifies how architectural design can respond to demands for restitution by physically hosting returned cultural property, thus countering the extractive histories of Western museums.

As Audre Lorde wrote,

“the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde, 2018).

These projects resist tokenistic diversity or symbolic decolonisation, instead offering practices of spatial justice and reparation. In this way, architectural intervention becomes not just aesthetic or functional, but ethical and political.

iv. Grounding Knowledge: Land, Place, and Truth-Telling

Land, as the foundational category of spatial practice, was framed in the seminar as a site of dispossession but also of knowledge and truth-telling. Sengupta and King referenced Maggie Walter’s claim that,

“truth-telling is place bound” (Hobart, 2023)

anchoring discussions of colonial land expropriation in specific geographies such as Wybalenna Cemetery on Flinders Island, Lutruwita/Tasmania. The architectural work by Taylor and Hinds at this site responds directly to the historical trauma embedded in the landscape.

Another example was the “Counter-Plantation Proposition” in Barbados by Mackenzie Luke (2023), which reimagines the Drax Estate, a site of plantation slavery, through a design language informed by the vernacular chattel house and anti-colonial aesthetics. These projects foreground the epistemologies of Indigenous and formerly colonised peoples, repositioning land as a living archive. This aligns with decolonial geographies, which insist on “grounding” theory in land-based struggles (Gilmore, 2022). Architectural truth-telling thus becomes an act of both historical reckoning and future-making.

v. Unarchiving the Built World: Buildings and ‘Things’ as Colonial Palimpsests

Lastly, the lecture proposed “unarchiving” as a critical practice for engaging with colonial material culture, not just buildings, but everyday objects, industrial sites, and architectural remnants. Swati Chattopadhyay’s concept of unarchiving was applied to projects such as the reinterpretation of the Crowther statue in Hobart (2024) and the design of the Malkha Cotton Factory in Telangana, India (Khandual, 2015), both of which challenge how colonial histories are stored, forgotten, or commemorated.

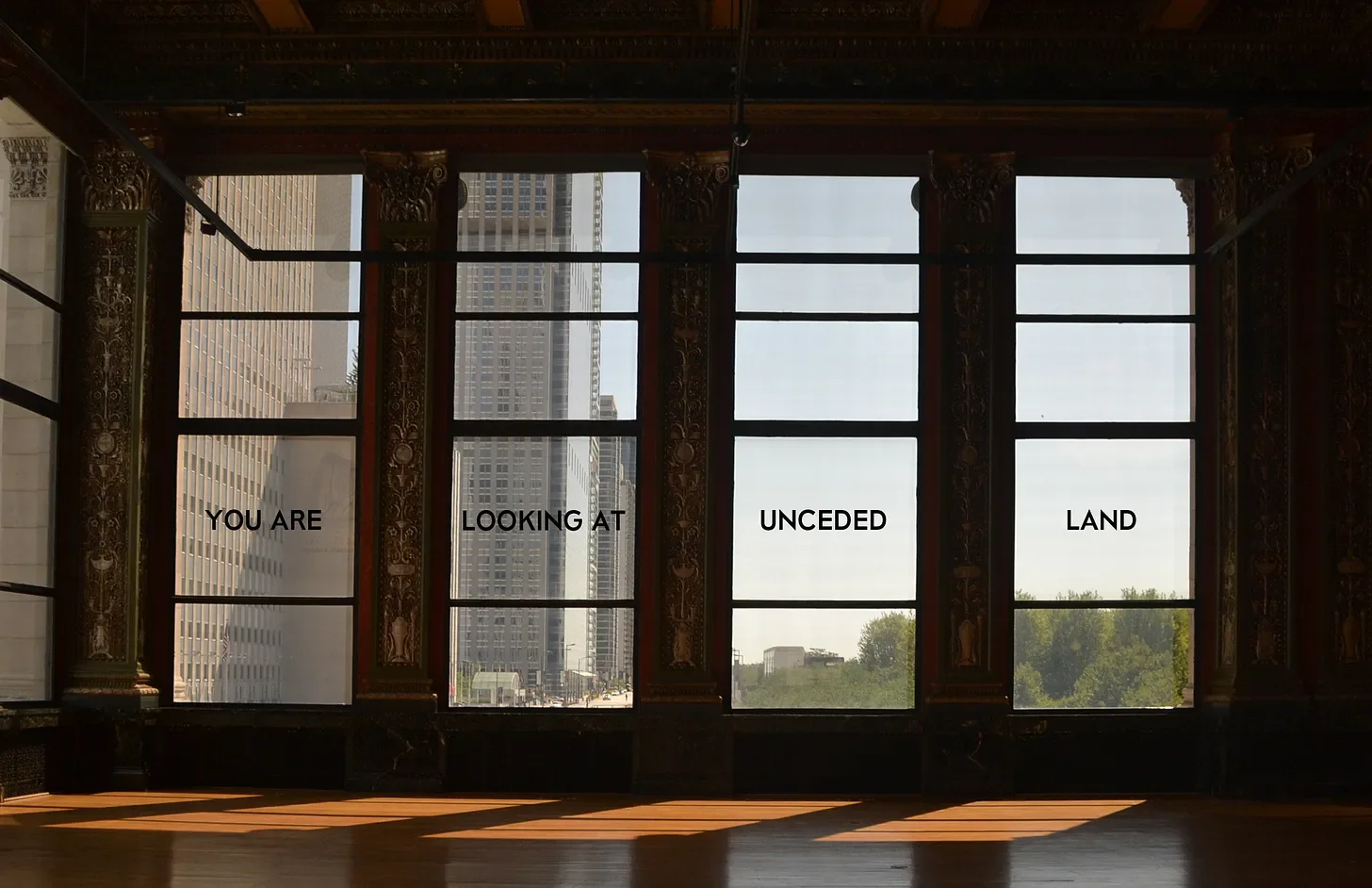

The Chicago Cultural Centre exhibition Settler Colonial City Project (2019) used text-based installations, “YOU ARE LOOKING AT UNCEDED LAND”, to name the structures of occupation and displacement that architectural practice often renders invisible. These practices expand the scope of architectural critique beyond buildings to include the “things” that compose them: materials, signage, museum artefacts, family memorabilia. Unarchiving, in this sense, becomes a form of design resistance, illuminating what Chattopadhyay (2023) calls,

“the structures of containment”

in the colonial archive. By destabilising dominant narratives, these works open space for counter-histories and alternative futures.

Conclusion

This seminar provided a rigorous and globally conscious framework for understanding how architecture operates as both a tool of colonial violence and a means of resistance. The inclusion of historical movements, decolonial theory, and contemporary case studies underscored the importance of addressing spatial justice through design. While the discourse itself may not be unfamiliar to those already engaged in questions of ethics and equity in architecture, the clarity with which the speakers framed these concerns, as embedded within every decision, material, and urban gesture, served as a necessary reminder of the political stakes of architectural practice.

Rather than seeking to “add” ethics to architectural work, the seminar reinforced the view that ethics are already always present, whether recognised or not. In the UK, this is especially urgent: the profession must move beyond surface-level gestures of inclusion to fundamentally reconsider the structures of commissioning, consultation, and authorship. Time, multiplicity of voices, and historical reckoning are not optional extras, but prerequisites for responsible practice. Clients must come to understand that meaningful engagement with colonial legacies demands more than symbolic design moves, it requires attention to lived histories, community memory, and the uneven geographies of harm and repair. Every architectural decision (however mundane) is ultimately a political one.

References

Aina, R.A. (2021) Museum for Repatriated Artefacts of Lobi Peoples. [Architectural Design].

Chattopadhyay, S. (2023) ‘Unarchiving: Towards a Practice of Negotiating the Imperial Architect’, Journal of Architectural Historiography.

Douglass, F. (1845) Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave. Webb and Chapman. National Library of Scotland.

Gilmore, R.W. (2022) Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation. London: Verso.

Hartman, S. (2019) Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. New York: Norton.

Lorde, A. (2018) The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House. London: Penguin.

Sengupta, T. and King, S. (2024) Reclaiming Colonial Architecture. London: RIBA Publishing.

Tuck, E. and Yang, K.W. (2012) ‘Decolonization is not a Metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), pp.1–40.

Walter, M. (2023) Speech at ‘Treaty, Voice & Truth Telling’, Hobart.