Who Are We Designing For? Architecture, Inclusion, and the Invisible User

Reclaiming the Human Centre in Design

Link to my Substack essay here

Architecture could be perceived to serve the human condition, through shelter, dignity, and to form the way live. Though, within the broader discipline, the conception of ‘the user’ often remains vague, abstract, and implicitly homogenous. Students are encouraged to design for an imagined inhabitant: rational, mobile, able-bodied, and culturally neutral. This figure, often referred to by feminist scholars as the ‘universal subject’, is less universal than Western, male, and privileged (Ahmed, 2017; Rendell, 2000). In centring such an archetype, architectural education risks perpetuating exclusion under the guise of neutrality.

Here we ask a perceptively simple question, who are we designing for?

Examining how the construction of the ‘average user’ erases multiplicity, and how frameworks from feminist geography, postcolonial theory, and critical disability studies can help reimagine architectural practice as plural, ethical, and attentive to difference. Drawing on theorists such as Doreen Massey, bell hooks, and Frantz Fanon, it argues that to design inclusively is not to design universally, but to accept the specificity of lived experience as a central design condition.

1. The Myth of the Universal User

Through the lens of architectural pedagogy, the concept of designing for ‘people’ often collapses into designing for an unmarked category, the imagined user who moves effortlessly through normative space. Feminist geographers such as Gillian Rose (1993) and Doreen Massey (1994) have shown that space is not neutral, that it is socially produced, inscribed with power, and gendered in its very construction. Still, architectural education tends to treat users as abstract data points, anthropometric figures, movement diagrams, or accessibility codes, rather than as socially and politically situated bodies.

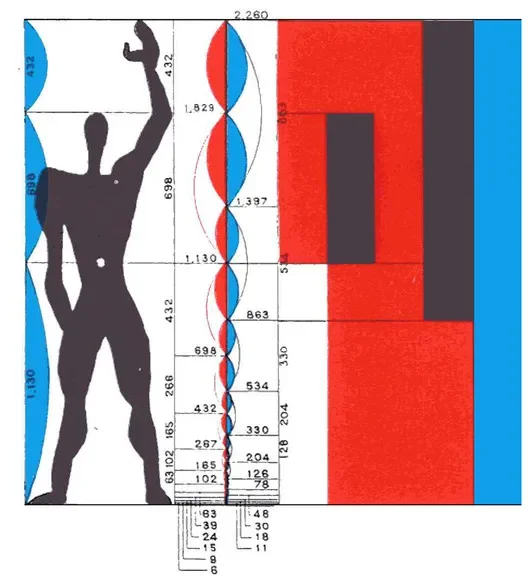

Le Corbusier’s Modulor Man (the six-foot-tall male figure used as a universal design scale).

This abstraction has historical roots. Modernism’s pursuit of universality and efficiency privileged standardisation and control. Le Corbusier’s ‘Modulor Man’ became emblematic of this mindset, a six-foot-tall European male body used as the measure of proportion and function. The feminist architect Jane Rendell (2000) observes, the Modulor does not simply represent a design tool but a worldview, one where human diversity is subordinated to idealised order. The supposed neutrality of such figures masks the exclusions they enact: women, disabled users, children, and those outside Western physical or cultural norms remain peripheral, both literally and conceptually.

Designing from a universal subject is therefore to reproduce a political stance disguised as technical precision. The task, then, is not to perfect the universal user, but to dismantle the assumption that universality should be the goal of design at all.

2. Feminist Geographies: Situated Knowledge and Embodied Space

Feminist geography challenges the neutrality of space by insisting on the importance of situated experience. Donna Haraway’s (1988) concept of ‘situated knowledges’ argues that all perception is partial, located, and embodied. Applied to architecture, this insight disrupts the illusion that designers can ever adopt an objective or omniscient perspective. Instead, it invites us to recognise our positionality (gendered, racialised, and cultural) as part of the design process.

Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative project (e.g. Jagonari Educational Resource Centre, London, 1987).

Doreen Massey’s (1994) work further reframes space as relational rather than fixed, a product of ongoing social interactions. Designing through this lens means conceiving of architecture as spatial encounter. For instance, feminist design collectives such as Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative (active 1980–1994) operationalised this relational thinking through participatory design methods. They worked with women’s groups to co-produce housing and community spaces, embedding difference into the very fabric of design. Their projects serves as a reminder that inclusion is a methodology, a practice of active listening and collaboration.

In architectural education, adopting feminist geography might mean redefining site analysis, mapping through terrain, context, patterns of care, safety, exclusion, and access. Who feels welcome in this space? Who avoids it, and why? These questions turn design away from an act of imposition to one of intent and inquiry.

3. Postcolonial Theory, The Colonial Residue of Neutral Space

If feminist geography exposes the gendered dimensions of spatial practice, postcolonial theory reveals its imperial ones. Architecture’s universalist language (order, beauty, function) emerged alongside colonial expansion and the global export of Western spatial norms. The modern city, as Frantz Fanon (1961) observed, was structured by segregation: “the colonist’s sector is a sector of lights and paved roads; the native’s sector, a place of darkness.”

Contemporary urbanism continues to bear this imprint. The grids, zoning laws, and masterplans of the twentieth century often reproduced colonial hierarchies of visibility and control. In architectural education outlined through the RIBA, this legacy persists in the Eurocentric canon, students continue to study the same Western architects while the spatial knowledge of Indigenous, African, and Asian traditions remains marginal.

Homi Bhabha’s (1994) concept of ‘hybridity’ provides a critical counterpoint, recognising that postcolonial identities are layered and adaptive. Designing through this lens encourages architects to think beyond imported typologies or aesthetic mimicry, towards architectures that reflect cultural negotiation. The growing movement to decolonise architectural curricula, seen in initiatives such as the Bartlett’s Decolonising Architecture group (2020), seeks to question not only what is taught, but whose knowledge counts. To decolonise design is therefore to expand the definition of the user. It requires acknowledging that architecture has often served to exclude and discipline, and that ‘public’ space has never been equally public for all. Recognising this history is a necessary step toward a more equitable design culture.

4. Disability and the Politics of Access

Critical disability studies further reveal how architecture defines belonging through the body. A building’s thresholds, heights, and pathways encode assumptions about movement and ability. Even when accessibility is legislated, it often appears as an afterthought, a technical adjustment rather than a philosophical stance. A ramp appended to a staircase does not undo the symbolic message that the stairs came first.

Tobin Siebers (2008) argues that disability should not be viewed as a deficit but as a form of embodied variation. From this perspective, inclusive design is not about accommodating exceptions but about redefining normativity. Sara Hendren’s (2020) notion of ‘prosthetic imagination’ expands this, describing design as a way of extending human capacity, where bodies and tools form mutual adaptations. Designing for disability, then becomes a mode of innovation rooted in empathy and interdependence.

This insight aligns with feminist ethics of care (Tronto, 1993), which prioritise responsiveness and relationality. Therefore an inclusive architecture never assumes a user, rather it asks, it observes, it adjusts. It treats access as a form of respect. In this light, the question ‘who are we designing for?’ becomes inseparable from ‘who gets to design?’ since representation within the profession shapes whose needs are even recognised.

5. Pedagogy and the Studio & Reframing the User in Education

Architectural education remains as one of the most influential sites where the concept of the user is formed. Studio briefs often describe occupants in minimal terms, “a family”, “a community”, “an office worker.” These placeholders flatten complexity into singular archetypes. As feminist pedagogue bell hooks (1994) insists, education that aspires to freedom must cultivate awareness of difference. To teach students to design inclusively, they must first be taught how see who is absent from their drawings.

Participatory design methods, ethnographic observation, and co-design workshops offer valuable pedagogical interventions. They move perceptions from imagining users to engaging them directly. This shift not only enriches the design process but destabilises the hierarchy between architect and inhabitant. The designer becomes facilitator as a listener. Critically, inclusion in education also demands structural change. Studies (Awan et al., 2011) highlight the persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities in architectural schools and leadership. Without diversifying who designs, discussions of for whom we design remain incomplete. Equity must operate both in content and in community.

6. Toward a Plural Ethics of Design

To design inclusively is to recognise aesthetics as inherently ethical, that every spatial choice affirms certain lives and neglects others. The future of architectural practice lies in its capacity to hold plurality; to build spaces that accommodate conflict, negotiation, and multiplicity. This plural ethics demands humility. Architects must accept that they cannot fully know their users, only approach them with curiosity and care. Doreen Massey (2005) reminds us that space is always “under construction”, a continuous becoming.

Designing for real users means designing for and with complexity: for the intersections of race, gender, disability, age, and culture that make up everyday life. It means understanding that architecture shapes life.

Conclusion

The figure of the ‘average user’ once offered architects a sense of universality, a comforting neutrality. Nevertheless, neutrality, as critical theory has shown, is itself a position one aligned with privilege. Reclaiming the human centre in design requires relinquishing the universal one. The work ahead is not about adding diversity as a layer, but reconfiguring the foundations of architectural thinking.

Who are we designing for? The answer is for many kinds of bodies, many ways of moving, many forms of belonging. Architecture must aspire to attentiveness, to seeing and hearing those long rendered invisible. In the end, inclusive design is stance, a commitment to seeing the user as a co-inhabitant.

References

Ahmed, S. (2017) Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press

Awan, N., Schneider, T. and Till, J. (2011) Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. London: Routledge

Bhabha, H. K. (1994) The Location of Culture. London: Routledge

Fanon, F. (1961) The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press

Haraway, D. (1988) ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp. 575–599

Hendren, S. (2020) What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World. New York: Riverhead Books

Hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge

Massey, D. (1994) Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Massey, D. (2005) For Space. London: Sage Publications

Puwar, N. (2004) Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. Oxford: Berg

Rendell, J. (2000) The Pursuit of Pleasure: Gender, Space and Architecture in Regency London. London: Athlone Press

Rose, G. (1993) Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge. Cambridge: Polity Press

Siebers, T. (2008) Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

Tronto, J. C. (1993) Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge