How Digitising Craft Shapes the Act of Making

On Attention, Influence, and the Quiet Ethics of Process

Link to my Substack Essay here

Learning to make has always depended on proximity. It could be argued that historically, learning a craft involved standing beside someone more skilled, watching closely, imitating gestures, failing quietly, and trying again. Today, that apprenticeship unfolds across screens and fragmented information. Each gesture, formerly slow and local, is now compressed into seconds and shared globally.

The internet has become a vast and open archive of technique. For those without inherited lineages or access to formal training, this accessibility is transformative. It allows individuals to learn outside institutions, connecting people through shared attention to process. But what it offers in reach, it risks solitude. When every act of making becomes content, even failure (ironically, the most formative part of craft) loses its privacy. The digital workshop rewards visibility over quiet repetition, and what disappears is the space to make mistakes unseen and to allow process mature before it performs.

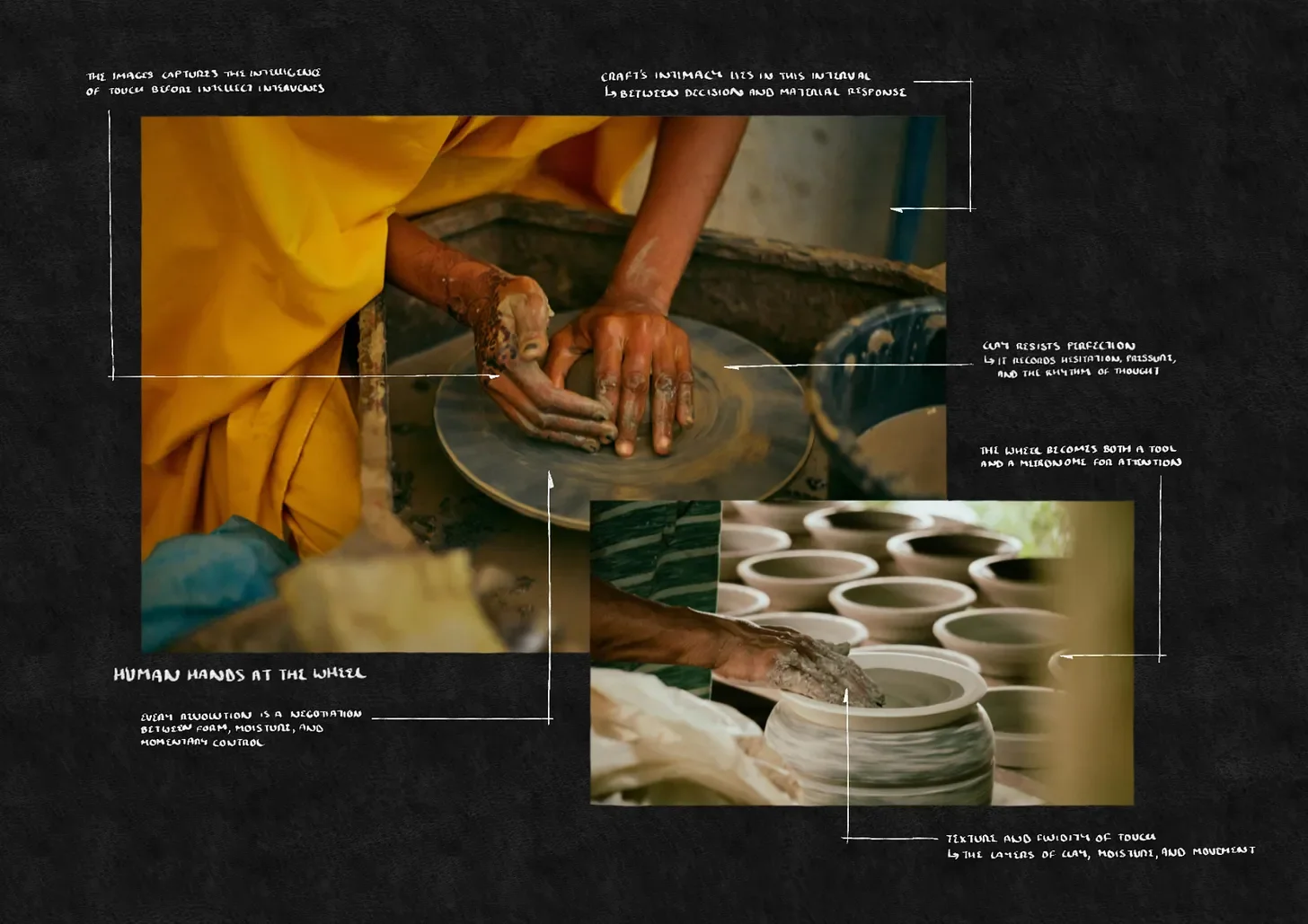

Close-up photography of a ceramicist’s hands centring clay on a spinning wheel, clay slipping between the fingers. Focusing on the tactile exchange between skin and material.

Making for the Feed

Craft has always been social a social act. Demonstration, apprenticeship, and repetition in front of others form its communal roots. Although, the omnipresent digital gaze transforms this exchange into a performance. Platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok turn this process into currency and measures of worth. The workshop environment becomes a stage, whereby the rhythm of the feed begins to dictate the rhythm of the hand.

Sociologist Richard Sennett (2008) describes craftsmanship as “slow mastery acquired through repetitive labour.” Although, online speed and spectacle dominate. What appears as skill may precede true understanding. The difference becomes temporal: mastery requires failure, revision, and return, while the algorithm privileges insatiable, immediate proof.

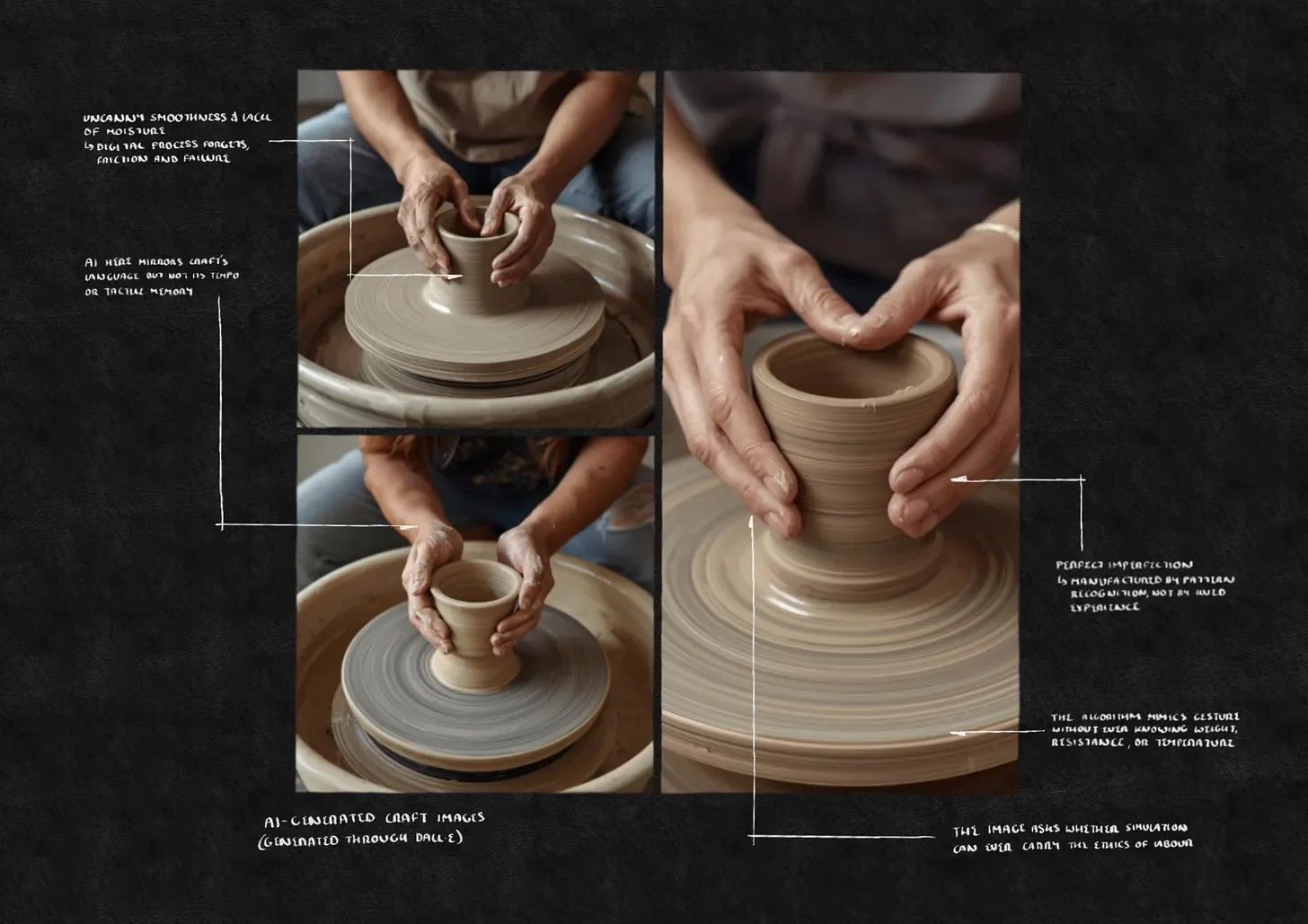

AI complicates this further. Generative tools can now simulate the gestures of design or shaping without touching material at all. Although, contractually this simulation can offers clarity rather than threat. If a machine can imitate process, it reminds us to protect what cannot be replicated. The value of slowness, tactility, and emotional intelligence.

Philosopher Minna Salami (2020) additionally argues that digital culture flattens depth into “surface reality.” When craft becomes image, it risks losing its temporal weight. Although, these surfaces also invite entry. For many, online visibility is the first step into making itself. The challenge is not rejection of the feed but disciplined participation in it, using exposure as a bridge.

Learning Without Proximity

For self-taught craftspeople, the internet could function as a kind of dispersed apprenticeship. Tutorials, forums, and recorded lectures replicate the exchange once found in shared workshops. The learner now has the ability to pause their learning environment, replay, and repeat, producing a mediated intimacy that still demands patience. Anthropologist Tim Ingold (2013) reinforces this by discussing making as an ongoing dialogue, not an act of control,

“We learn not by imposing form, but by listening to what the material allows.”

This active listening can happen through a screen, provided attention remains intact.

Additionally, Bell hooks (1994) called education “the practice of freedom”, a process of choosing to learn. Digital craft education, at its best, embodies that freedom, enabling learners to move horizontally across geographies and traditions. But freedom online also requires a level of self-discipline and critical thinking. Algorithms can as easily dilute attention as they can direct it. The distinction lies in intentionality: searching, tracing histories, and following lineages turns the internet into a resource.

Algorithmic Authorship

Posting online transforms every craftsperson into an unwitting designer of data. Algorithms learn from our patterns, turning handmade gestures into digital templates. As Glenn Adamson (2013) argues that craft historically resists replication; it values human variation and error. Platforms, however, thrive on predictability, absorbing the idiosyncratic until it becomes standardised.

In architectural terms, it’s as if the blueprint redraws itself mid-build, optimising for efficiency rather than expression. Soetsu Yanagi (1959) argued that “The beauty of imperfection comes from the heart that is free.” Online, that freedom requires deliberate resistance, posting irregularly, embracing unphotogenic work, and aggressively prioritising individual rhythm over reach. These gestures reclaim individual authorship from the algorithm and remind us that meaning often lives in the inefficient.

Between Connection and Consumption

Digital spaces have also democratised craft. Providing access and community that traditional structures have denied. Comment threads can become smaller workspaces for feedback, repair, and ongoing encouragement. Conversely sharing can become a form of performance, whereby duration is lost. A bowl thrown, filmed, and scrolled past may live shorter than the time it took to even centre the clay.

Psychologist Sherry Turkle (2011) discusses that, collectively, we have come to,

“-expect more from technology and less from each other.”

Still, the visibility of process online can reignite a collective desire to make. Watching a bowl being thrown may never equal holding it, but it might prompt and encourage the observer to try. The question is not authenticity versus artifice, but intention: do we use the digital to deepen practice, or to replace it?

AI-generated images of a pair of hands throwing on a pottery wheel. The grain too smooth, the light too symmetrical, the hands slightly imprecise, and almost a complete lack of water.

(Generated through DALL·E)

Reclaiming Digital Craft

The digital hand is not a copy of the human one, but acting as an extension of it. Working ethically online is to treat digital space as a notebook rather than a stage. Sharing ongoing questions, not singular outcomes. Thereby actively posting mistakes, hesitations, slow progress, as a militant act of assembly.

A process documented over months resists the tempo of the feed or someone else’s agenda. A project that refuses optimisation invites genuine reflection, for the observer and the craftsperson. As in architectural conservation, the ethics of digital making are grounded in care, the care for material, for process, and for one’s own rhythm. The purpose if to inhabit technology differently.

Conclusion: Toward Digital Stewardship

Craft will continue online because it must. The choice lies in how it does so, as a performance or as practice. To make digitally is not about abandoning authenticity but a participation to now, redefine it. As the conservator respecting the patina of a wall, the digital maker respects the time embedded in process.

Additionally, AI will not end making. Instead, it may offer clarification on what remains irreplaceable. Additionally, on how these are not inefficiencies, but are the core of craft.

Conclusively as this discussion evolves, the digital and human hands are not opposites but interlocutors. The screen can be a mirror, if we look at it with our engaged and critical attention.

References

Adamson, G. (2013) The Invention of Craft. London: Bloomsbury.

Hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

Ingold, T. (2013) Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

Salami, M. (2020) Sensuous Knowledge: A Black Feminist Approach for Everyone. London: Zed Books.

Sennett, R. (2008) The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Turkle, S. (2011) Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books.

Yanagi, S. (1959) The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty. Tokyo: Kodansha International.