How to keep learning when nobody’s telling you to

On finding education in what survives, adapts, and endures.

Link to my Substack Essay here

Something I’ve learned (slowly, and mostly after leaving university) is that education doesn’t end when you hand in your final piece of work. For many, it truly begins afterwards, in the long, quiet process of unlearning, re-reading, reconnecting to what they chosen architecture for in the first place.

Architecture is a lifelong conversation between yourself, buildings, materials, histories, and the world as it changes. And if you stop listening, stop reading, stop looking, you actively lose your voice in that conversation.

Architecture is a demanding discipline. It consumes your entire existence. The idea of adding more (more reading, more research, more reflection) feels unbearable, like scraping an empty barrel. But self-education is not about adding weight; it’s about lightening it. It’s about finding what resonates, tracing a thread through the immense fabric of architectural history and conservation until you find the part that feels alive. That’s where your own curriculum begins.

1. Why self-education matters more than ever

Formal education gives you a framework: modules, deadlines, criteria, a reading list you may or may not ever read. These structures and boundaries form your early understanding of architecture, but what happens when that framework ends? Who sets your next brief? Who marks your work when you’re no longer being graded?

The uncomfortable truth (or, for some, the liberating one) is that nobody does. And that’s exactly the point.

When you leave your formal education, learning becomes an act of agency. You’re no longer producing for a system; you’re learning to listen to yourself, to the buildings around you, and to the cultures that made them.

In the field of architectural conservation, this autonomy becomes quite essential. Conservation asks us to interpret it through our own lens. You navigate between history and contemporary demand, between the physical matter of a wall and the invisible social histories embedded within it. To do that well, you to become actively curious, and curiosity doesn’t always survive long under prescription.

As Sally Stone (2019) writes in Undoing Buildings: Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory, “Conservation is not about freezing the past, but about continuing the story.” If you stop educating yourself, the story stops too.

2. Building your own curriculum

A self-curriculum doesn’t need a timetable or a course code. It can begin with something that interests you, filtered into one question, one building, one sentence that unsettles you. The aim isn’t to just collect knowledge, and to store it away, it’s to create friction with your own identity.

Start with Deyan Sudjic’s The Edifice Complex (2005) and feel the weight of architecture as an instrument of power, and the ways that buildings become political theatre. Then read Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment (Boys et al., 2022) and realise that power is not just monumental, but gendered. Move to Thomas Heatherwick’s Humanise (2024) and think about materiality, emotion, and the politics of “human-centred design”. And then question him too, for the privilege and contradictions embedded in that position.

The more you challenge yourself, the more you understand what you actually believe.

Research should disagree with you. The purpose of a personal curriculum isn’t passive comfort; it’s active confrontation.

3. Architectural conservation as self-education

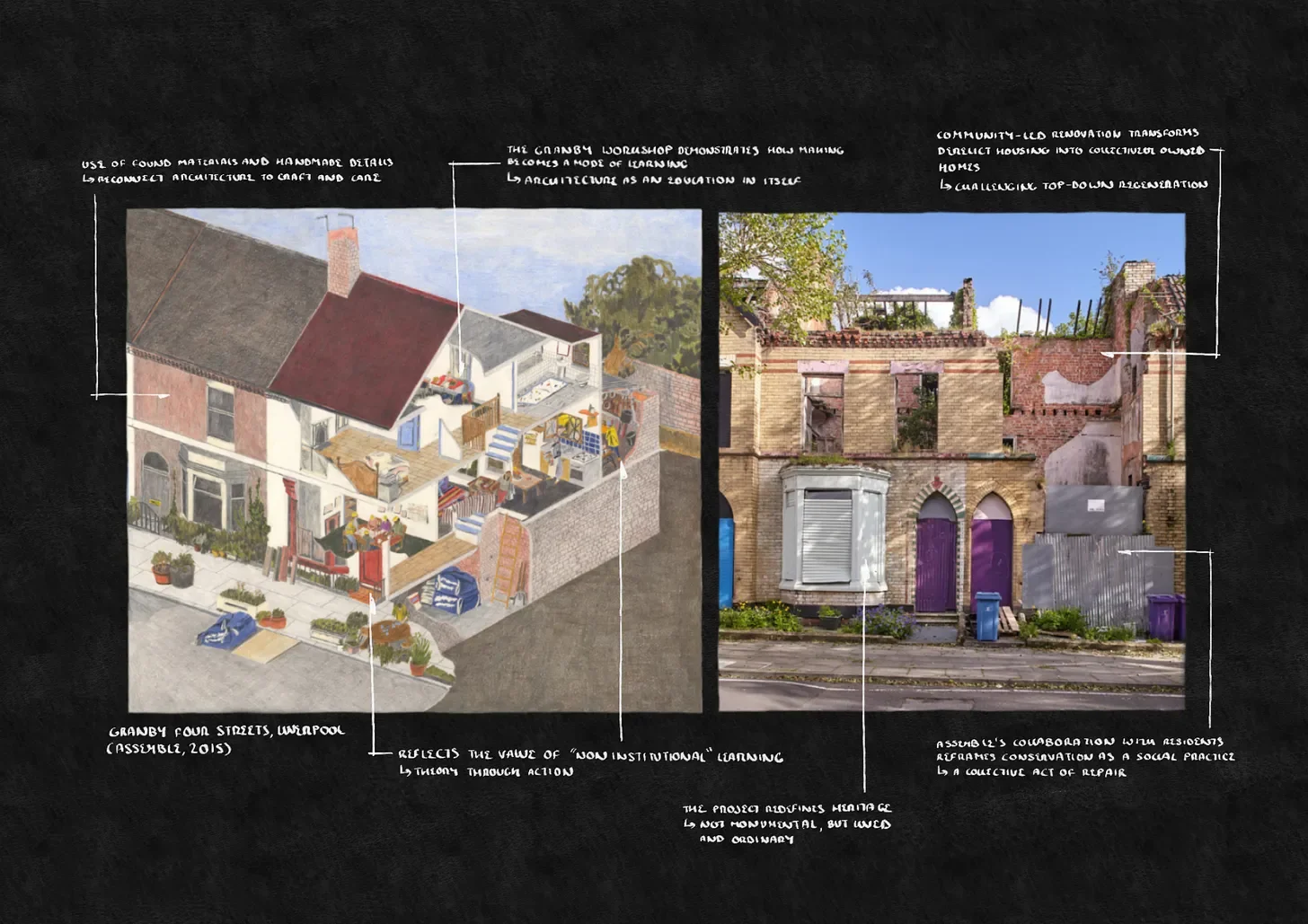

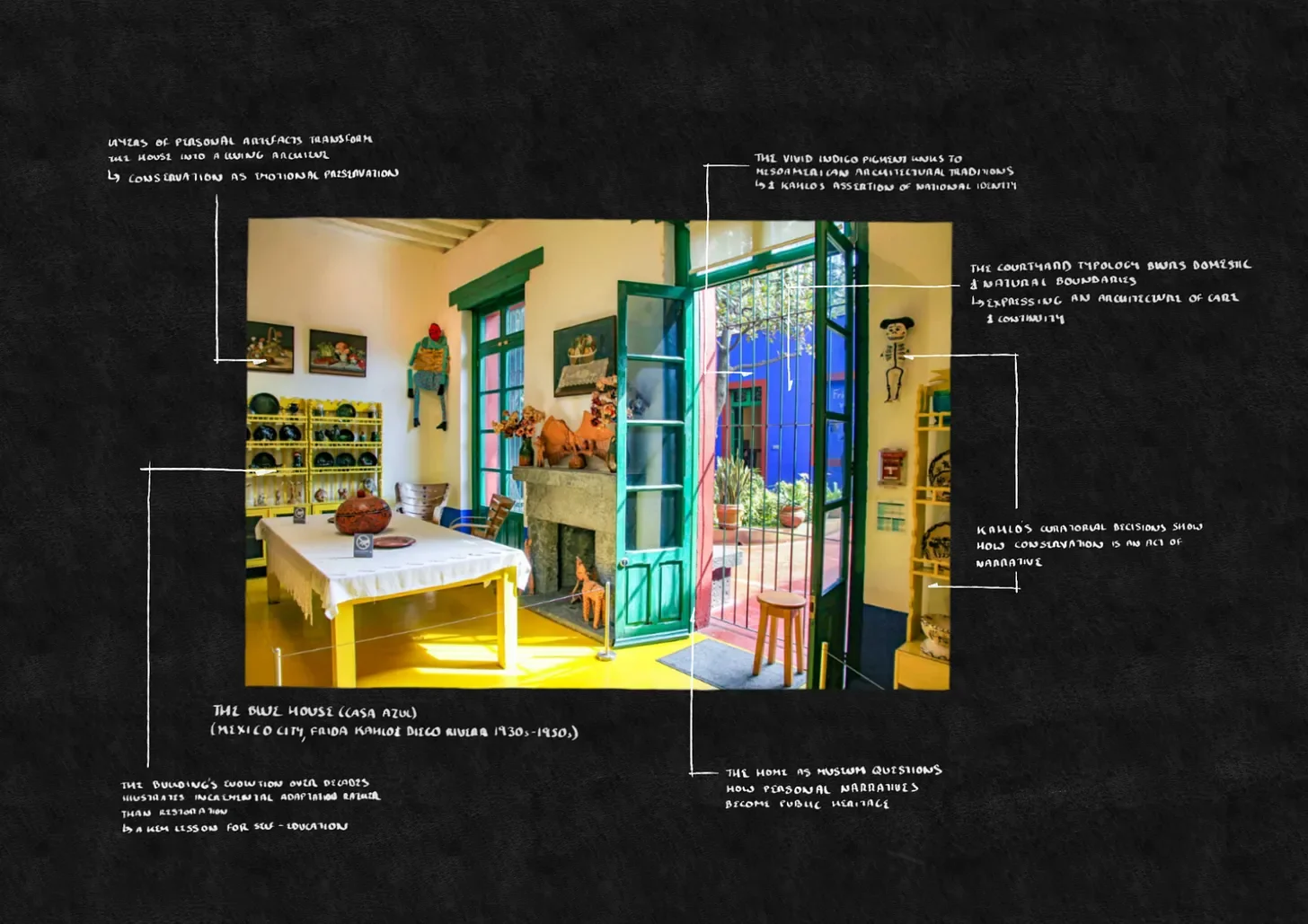

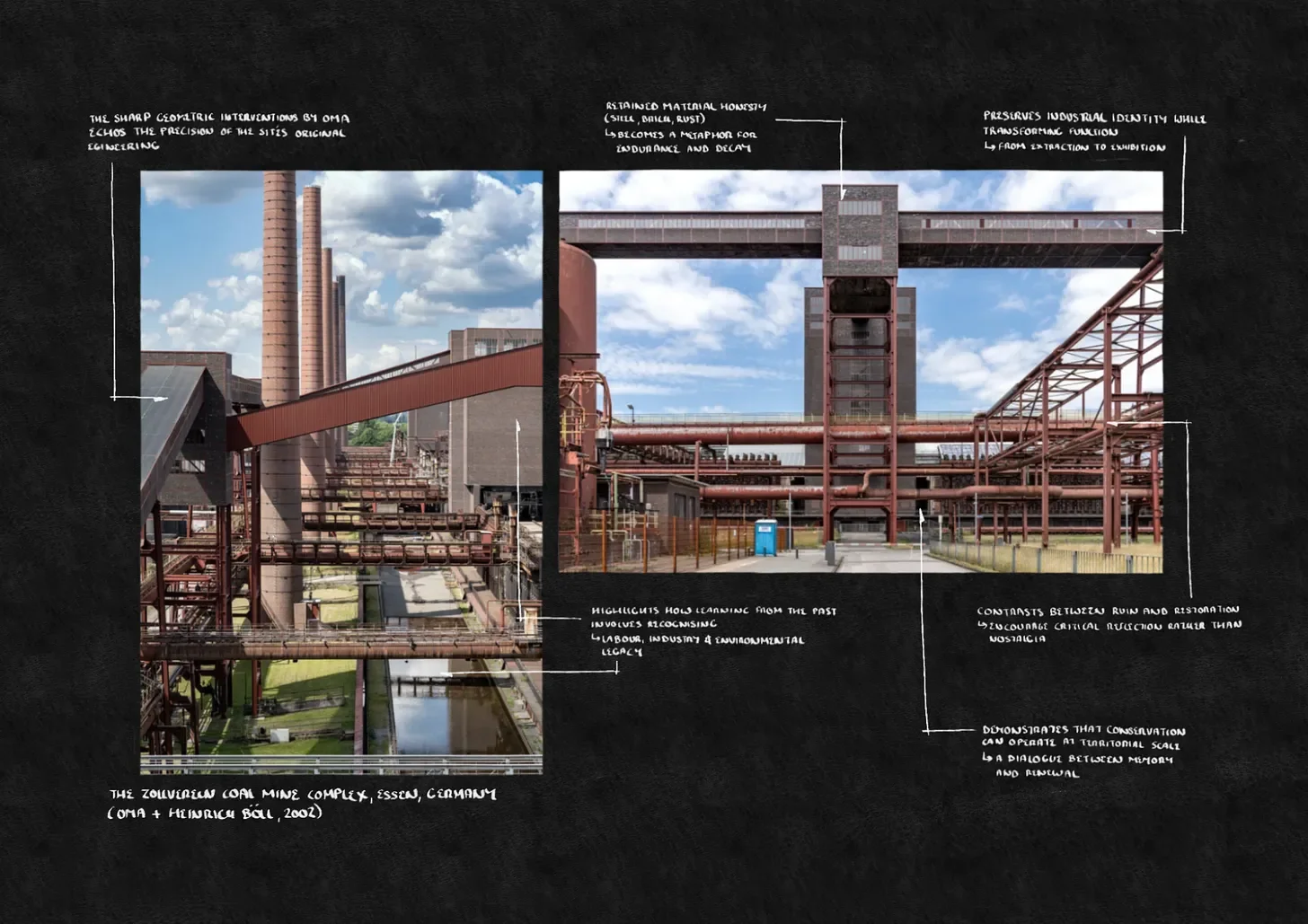

Conservation as a field and subject isn’t about romantic nostalgia. It’s about a hidden dialogue. Every building you work with is a record of choices, compromises, and ambitions acting as a document of its own making. Studying conservation means studying people and communities: their politics, their economies, their mistakes.

To treat conservation as merely technical, as a checklist of materials and methods, is to misunderstand its purpose. It is, at its heart, an ethical and intellectual practice.

When you decide what to keep, what to alter, and what to erase, you’re making decisions about whose history is allowed to remain visible.

Sally Stone (2019) explains how, “the act of conservation must always be an act of translation.” When you adapt or reuse a building, you translate history into the present moment. And translation is never neutral. What you choose to preserve or discard exposes your values, you’re beliefs, you’re views, and you’re bias.

Therefore, building your own curriculum around conservation provides you the opportunity to explore those values openly and freely. You might begin with Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage (Plevoets and Van Cleempoel, 2019), then move to Undoing Buildings (Stone, 2019), and then outwards; to texts on urban sociology, ecology, feminist geography, or postcolonial studies. Which might seem counterintuitive, but this is because to understand a building, you have to understand the world that built

4. Learning without institutions

Universities position themselves as the custodians of knowledge. But the truth is that their frameworks are tightly bound to the expectations of professional bodies like the RIBA and ARB. These systems dictate how courses are structured, assessed, and validated. There is little room for deviation, and for exploring outside what counts as “architecture” within that system.

Self-education, on the other hand, gives you freedom of your own agency. It lets you expand your understanding beyond accreditation, beyond professional templates. You can study a building because it fascinates you, not because it appears on a module guide.

Learning this way is more expansive. Don’t confine yourself to an entirely written based curriculum either, you might explore the use of photography by photographing your local street and tracing how the buildings talk to one another. It might mean visiting derelict sites and asking who used to live or work there. It might mean interviewing residents, or sketching material details, or documenting the unnoticed.

To study conservation this way is to cultivate empathy, and to approach architecture through lived experience. You will then learn by walking, by touching, by asking questions that can’t always be answered. There’s a quiet liberation in knowing you don’t need institutional permission to care.

5. Reading lists as acts of resistance

Every curriculum carries bias. Most architectural reading lists remain white, male, and Eurocentric. Universities are beginning to address this under the banner of “decolonising the curriculum,” but progress is slow, limited by the same systems that determine what counts as academic.

To construct your own curriculum, then, is an act of resistance. It’s a way of rebalancing what voices you listen to, and therefore how you think.

I initially developed my own self-education in architectural conservation has drawn from:

Sudjic, D. (2005) The Edifice Complex: The Architecture of Power

Boys, J. et al. (2022) Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment

Heatherwick, T. (2024) Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World

Stojanovic, D. (2023) Architecture for Housing: Understanding the Value of Design

Stone, S. (2019) Undoing Buildings: Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory

Plevoets, B. & Van Cleempoel, K. (2019) Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage

Wong, L. (2017) Adaptive Reuse in Architecture: A Typological Index

Open Heritage: Community-Driven Adaptive Reuse in Europe (2021)

But it also reaches beyond architecture.

Bell hooks’ Teaching to Transgress (1994) reframes education as liberation.

Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (2013) reconnects making with ecology.

Arundhati Roy’s essays remind us that space is always political.

And for fiction (from Toni Morrison to Italo Calvino) teaches more about the human experience of space than many architectural texts ever could. Fiction reminds us that people and buildings coexist, that the spaces we make are inseparable from the lives that unfold within them.

6. From Research to Reflection

There’s a difference between being assigned an essay and writing because you need to think. When you create your own curriculum, you’re not writing to prove what you know; you’re writing to find out what you think, you’re actively meeting yourself.

Begin academically if you need structure. Choose a conservation question, How does adaptive reuse act as a form of cultural memory?, and approach it formally: literature review, methodology, references, word count. Then, when it’s done, rewrite it without formality.

Ask: what surprised me? What stayed with me? What did I disagree with?

That second version, you’re reflective, personal one, is where real learning happens and where you truly meet yourself. It’s where education shifts from extraction (collecting information) to transformation (changing how you see).

So why does this matter? Because when you stop thinking critically, when you let your curiosity dull, you start designing by habit. And architecture built by habit loses its soul.

7. Lifelong Context and Responsibility

Architecture itself doesn’t exist in isolation, and neither should you’re learning. Self-education is an act of responsibility; to the context, to the community, to history. Every conservation decision, every adaptive reuse project, is entangled with human lives, and to think otherwise removes the individual.

As Heatherwick (2024) argues, architecture can “nourish or deaden the senses.” As Sudjic (2005) warns, it can seduce or oppress. The difference lies in awareness, in the decision to stay awake to your environment.

When you approach learning this way, it stops being an obligation and becomes a way of living, as an act of attention.

When exploring, the interesting part is that you can explore conservation through your own personal heritage, your language, or your locality. Study vernacular architecture. Speak to craftspeople. Ask how buildings were made, what materials were valued, what rituals shaped construction. Don’t just study the technical and explore how you can lift these techniques, be curious, and explore the why.

Conclusion | Education as continuity

If you want to understand architecture, truly understand it , you have to see it as a lifelong act of reading, researching, and reflecting. Not because it earns you credits or validation, or another degree, but because it keeps you alive and engaged in a sometimes grey world.

Additionally, architectural conservation teaches this more clearly than any other field. It shows that nothing is ever finished: every building is a draft, every idea a continuation.

So, write your own curriculum. Read beyond your comfort. Challenge your assumptions. Walk through buildings and listen to what they’re still trying to teach you.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1986) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Boys, J. et al. (2022) Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment. 3rd edn. London: Verso.

Heatherwick, T. (2024) Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World. London: Penguin.

Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Plevoets, B. & Van Cleempoel, K. (2019) Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage: Concepts and Cases of an Emerging Discipline. London: Routledge.

Schön, D. A. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. New York: Basic Books.

Stone, S. (2019) Undoing Buildings: Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory. London: Routledge.

Sudjic, D. (2005) The Edifice Complex: The Architecture of Power. London: Penguin.

Wong, L. (2017) Adaptive Reuse in Architecture: A Typological Index. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Open Heritage: Community-Driven Adaptive Reuse in Europe (2021) European Commission.