The Architecture You Don’t See: Black Women, Craft, and Vernacular Knowledge

Black Women, Building Traditions, and the Politics of Heritage

Link to my Substack essay here

Architecture is framed as the art of designed and monument, a the product of vision, authorship, and permanence. Although, beneath this lie histories of making that have rarely entered the architectural archive. Black vernacular architecture, the building traditions of African-descended peoples shaped through enslavement, migration, and colonialism, embodies a form of architectural knowledge that is profoundly spatial and intelligent. These architectures emerged from collective labour, environmental adaptation, and craft-based knowledge. They are rarely attributed to named designers, often transmitted through oral teaching, embodied skill, and intergenerational practice.

Crucially, women have been at the centre of these traditions, as the builders, decorators, and custodians of maintenance. Although their contributions have been doubly erased: first by colonial and racial hierarchies that dismissed vernacular production, and second by patriarchal conceptions of architecture that privilege authorship over collaboration. This essay argues that Black vernacular architecture, and particularly the craft-based practices of Black women, constitute a vital architectural lineage, one that challenges the Western discipline’s assumptions about authorship, permanence, and value. Drawing from feminist geography, postcolonial theory, and heritage studies, it situates Black women’s craft as both cultural continuity and political resistance.

(Early 20th-century Gullah clapboard dwelling with expansive porch for communal living)

1. Defining Black Vernacular Architecture through Context and Characteristics

Black vernacular architecture describes building practices developed within African diasporic and postcolonial contexts, characterised by their collectivist and adaptation to environment. Unlike contemporary architecture, it is grounded in lived knowledge rather than codified theory. Argued by Upton (1986), vernacular building are “the architecture of everyday life,” a mode of social expression rather than stylistic imitation. Within African diasporic contexts, this everydayness is historical, originating from forced displacement and, racialised labour.

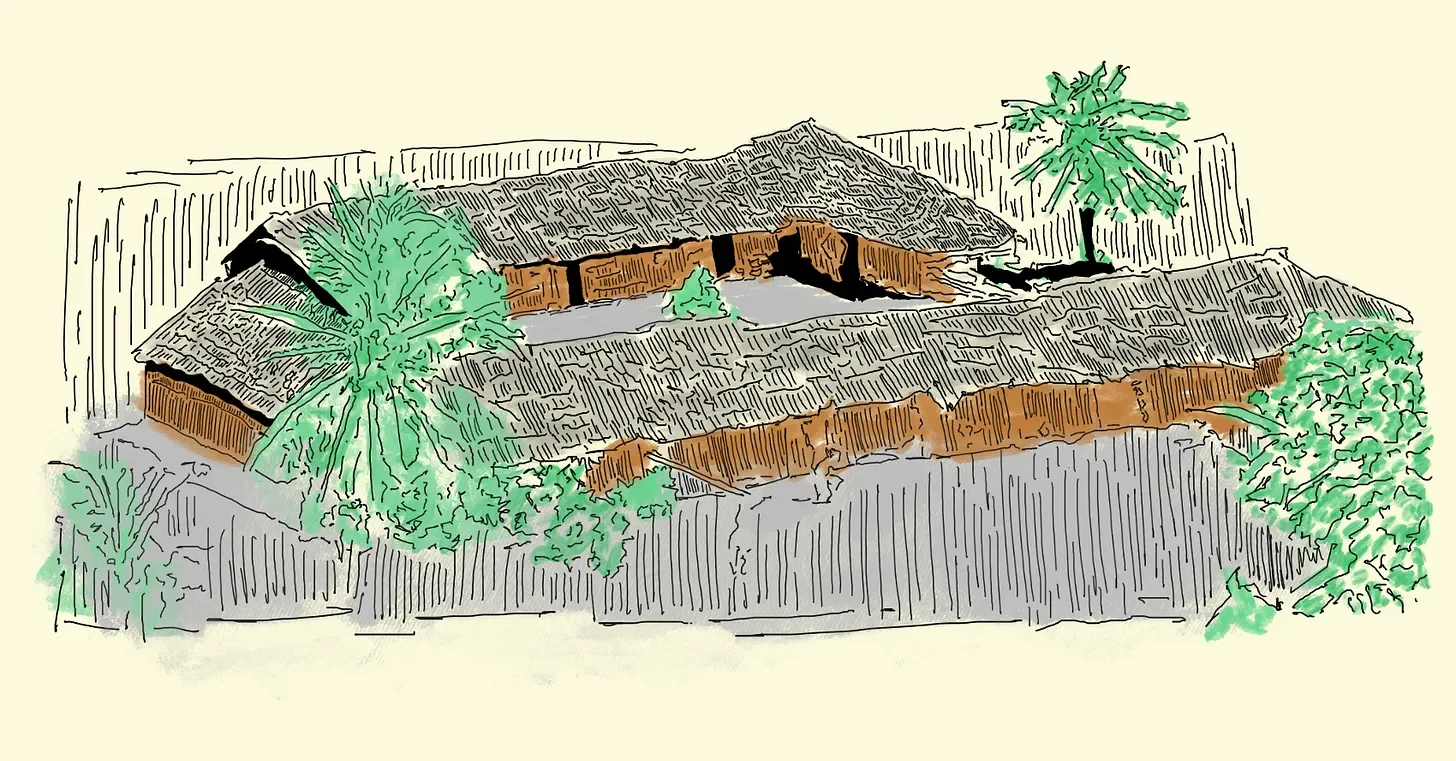

Examples abound across geographies. The Gullah-Geechee settlements along the U.S. South Atlantic coast demonstrate the persistence of West African building logics, with raised timber homes, tabby concrete made from oyster shell, and wattle-and-daub walls (Vlach, 1993). These structures were collectively produced, reflecting both climatic adaptation and cultural resilience. Similarly, the Maroon settlements of Jamaica and Suriname developed defensive landscapes and communal compounds as acts of freedom, spatial declarations of autonomy in resistance to colonial domination (Bilby, 2005). Across West Africa itself, Hausa, Yoruba, and Ashanti compounds demonstrate a sophisticated environmental intelligence, constructed from earth, timber, and thatch, and maintained through cyclical craft labour, often led by women (Prussin, 1986; Denyer, 1978).

(Exterior of Gullah tabby house showing oyster-shell concrete foundations in Lowcountry context)

These traditions reflect material pragmatism, while also encoding social and spiritual meaning. Whereby building becomes a way of knowing, as a dialogue between human, material, and environment. As Gilroy (1993) theorises in The Black Atlantic, diasporic culture is defined by movement and hybridity rather than rooted singularity. Black vernacular architecture similarly manifests this hybridity, neither purely African nor Western, but a synthesis shaped by displacement.

By recognising these forms as the legitimate architecture they are, and not only as anthropology, we are actively challenging the professional canon that historically marginalised them. A vernacular building is plural, an ongoing negotiation between necessity and care. This enriched understanding provides the foundation for examining the gendered dimensions of Black vernacular practice.

2. Women, Craft, and the Architecture of Maintenance

Women have historically occupied central roles in African and diasporic building cultures, as architects in practice if not formally recognised in title. In a West African context, the cyclical renewal of earthen architecture depends upon the craft labour of women’s collectives. Hausa and Ashanti women are renowned for their annual replastering and ornamentation rituals, in which walls are remade and repainted after the rains (Prussin, 1986). These acts, are often dismissed by colonial observers as domestic decoration, constitute vital architectural maintenance and environmental adaptation.

(Hausa house facade in Zaria, Nigeria: patterned mud-plaster decoration from women’s craft labour)

Additionally, feminist scholars have long argued that care and craft are forms of design; Tronto (1993) describes care as a political ethic, “a practice that sustains life.” Within vernacular architecture, women’s labour sustains structures and social continuity. Through the mastery of plastering, painting, and spatial upkeep, they perform what Matory (2005) terms “the social reproduction of the sacred,” maintaining material and symbolic coherence across generations.

From a feminist perspective, this labour challenges architecture’s gendered hierarchies of value. As Rendell (2000) observes, the Western discipline privileges creation over maintenance, design over use. In contrast, Black women’s craft traditions merge creation and care, design as ongoing, relational process. Bell hooks (1994) conceptualises this as an “aesthetic of survival,” where the domestic sphere becomes a site of resistance and reimagination. In this sense, the replastered compound wall or rethatched roof is not simply maintenance; it is the architecture of endurance.

These practices embody an epistemology, a knowledge transmitted through doing. They represent what Haraway (1988) would call “situated knowledges,” grounded in lived experience. Through women’s craft, architecture is revealed as a collective verb rather than a static noun. This recognition compels a broader reconsideration of what, and who, constitutes architectural expertise.

3. Colonial Erasure and the Politics of Recognition

Despite their sophistication, Black women’s vernacular architectures have historically been excluded from architectural discourse. This exclusion is not accidental, it is structural, rooted in colonial and patriarchal definitions of architecture itself. Western architectural theory, from Vitruvius to Le Corbusier, has privileged permanence, authorship, and monumentality, qualities rarely applicable to community-built, perishable, or anonymous forms (Anthony, 2001).

(Detail of mud-wall surface with geometric motifs; craft as architectural authorship)

Colonialism compounded this hierarchy. Within imperial ethnography, African and Caribbean architectures were recorded as curiosities rather than as legitimate design systems (McClintock, 1995). The anthropological gaze categorised them as “vernacular” or “native huts,” denying them their architectural status. Fanon (1961) noted that colonial space was materially and symbolically divided, that the coloniser’s city of light and order against the colonised’s city of improvisation and decay. Architectural knowledge was thus racialised, order and geometry attributed to Europe, improvisation and craft to Africa.

Women’s authorship was therefore doubly marginalised. As Lesley Lokko (2000) argues, the Western canon equated architecture with masculine genius, leaving no room for the communal and the domestic. Consequently, Black women’s building traditions were rendered invisible through this misclassification. They existed, but outside the disciplinary frame.

These exclusions persist throughout and within education. Awan, Schneider, and Till (2011) demonstrates how architectural curricula remain dominated by Eurocentric precedents, erasing non-Western spatial knowledge. Decolonising the discipline therefore requires more than diversifying case studies, it demands redefining architecture’s epistemic foundations. Recognising Black women’s craft as architectural is a political act, and reclaims authorship from the margins and reframes maintenance, care, and collectivity as central design principles.

4. Diaspora, Adaptation, and the Aesthetics of Survival

Across the African diaspora, Black women’s vernacular knowledge continued to evolve through adaptation. Migration, displacement, and urban marginalisation gave rise to hybrid spatial practices that reinterpreted tradition within new geographies.

In Britain, post-war Caribbean migrants (many of them women) transformed public housing into spaces of cultural identity. Forde (2018) documents how domestic interiors became sites of diasporic expression through colour, pattern, and ornamentation. These acts of redecoration re-inscribed council flats with Caribbean aesthetics, reclaiming belonging within an often-hostile urban environment. Similarly, Gilroy’s (1993) The Black Atlantic describes how diasporic subjects create continuity through cultural practice, whereby the home becomes a vessel of memory and negotiation.

(Interior of diasporic home, how Caribbean craft traditions repurposed in British domestic architecture)

In the United States, African-American women sustained vernacular craft traditions within domestic and community architecture. Walker (1990) traces the lineage of Black women builders in the postbellum South, many of whom maintained rural construction practices while adapting to urban conditions. Their work, often uncredited, shaped the visual and spatial fabric of Black neighbourhoods.

These examples demonstrate what hooks (1990) calls “homeplace”, a spatial politics of resistance in which Black women construct environments of care against systemic devaluation. Architecture here is not a performative grand commission, rather is the act of claiming space. Material adaptation (reusing timber, reconfiguring layouts, painting façades) becomes cultural inheritance and an assertion of presence.

(Detail of Caribbean-influenced decorative surface in UK home; craft as spatial agency)

Such practices exemplify an “aesthetics of survival” (Hooks, 1994), beauty as resilience and ornament as declaration. They also destabilise professional categories, where the line between craft and architecture dissolves, and the domestic becomes a site of innovation and self-definition. Through these acts, Black vernacular architecture endures as a living, adaptive form.

5. Toward a Decolonial Feminist Architecture

Recognising Black vernacular traditions requires rethinking architecture’s epistemology. Decolonial feminist theory provides one framework for this reorientation. María Lugones (2010) critiques how coloniality structured not just racial hierarchies but gender itself, producing what she terms “the coloniality of gender.” Within architecture, this manifests in the exclusion of racialised and feminised knowledge from legitimate design discourse.

Decolonial practice, therefore, is transformative. Mignolo (2011) calls for “epistemic disobedience,” the refusal to reproduce Western hierarchies of knowledge. In architectural terms, this means valuing embodied, local, and oral forms of expertise. Lesley Lokko’s (2023) work at the African Futures Institute exemplifies this shift, proposing an “architecture of multiplicity” rooted in narrative and craft rather than universal form.

Contemporary practitioners and scholars are becoming more aware and are beginning to bridge these lineages. David Adjaye’s projects often draw on vernacular African typologies, translating communal spatial principles into contemporary form (Adjaye, 2011). Although the deeper decolonial task lies beyond aesthetic reference, and involves structural recognition of those historically excluded from authorship. A decolonial feminist architecture learns from the methodologies of vernacular craft, through slowness, collectivity, repair. It understands design as stewardship rather than control. In this sense, the hands of these builders are not prophetic, modelling an architectural ethic grounded in care and endurance.

Conclusion

Black vernacular architecture reveals that the act of building is never neutral. It encodes histories of migration, resistance, and collective knowledge. Within these traditions, Black women’s craft emerges as architecture in its most essential form as responsive, adaptive, and ethical. Their work resists erasure not through maintenance, and not through authorship but through continuity.

The Western discipline, which has long preoccupied with universality and authorship, still has much to learn from these vernacular epistemologies. To decolonise architecture is, therefore, to expand its definition by including the courtyard replastered each season, the diaspora home adorned with inherited patterns, the walls remade by many hands.

In recognising these architectures, we are doing more than correct an omission, we actively redefine what architecture can be. Black women’s vernacular craft is not the margin of architecture, it is its entire foundation. As a reminder that building is always a collective act, that architecture is a form of care, and that heritage lives in the hands that sustain it.

References

Adjaye, D. (2011) Adjaye, Africa, Architecture: A Photographic Survey of Metropolitan Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson

Anthony, K. (2001) Designing for Diversity: Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Architectural Profession. Urbana: University of Illinois Press

Awan, N., Schneider, T. and Till, J. (2011) Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. London: Routledge

Bilby, K. (2005) True-Born Maroons. Gainesville: University Press of Florida

Chambers, I. (2001) Culture after Humanism: History, Culture, Subjectivity. London: Routledge

Denyer, S. (1978) African Traditional Architecture: An Historical and Geographical Perspective. London: Heinemann

Fanon, F. (1961) The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press

Forde, K. (2018) ‘Reclaiming Home: Caribbean Women and the Domestic Aesthetic in Britain’, Journal of British Cultural Studies, 29(3), pp. 412–429

Gilroy, P. (1993) The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Haraway, D. (1988) ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp. 575–599

Hooks, b. (1990) Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Boston: South End Press

Hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge

Lokko, L. (2000) White Papers, Black Marks: Architecture, Race, Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Lokko, L. (2023) African Futures Institute: Manifesto. Accra: AFI Press

Lugones, M. (2010) ‘Toward a Decolonial Feminism’, Hypatia, 25(4), pp. 742–759

Matory, J. L. (2005) Black Atlantic Religion: Tradition, Transnationalism, and Matriarchy in the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé. Princeton: Princeton University Press

McClintock, A. (1995) Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge

Mignolo, W. (2011) The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Prussin, L. (1986) Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press

Tronto, J. (1993) Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge

Upton, D. (1986) ‘Vernacular Domestic Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Virginia’, Winterthur Portfolio, 21(2/3), pp. 95–119

Vlach, J. (1993) Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press

Walker, S. (1990) Homegirls: Contemporary Black Women Builders in the American South. New York: Doubleday